The human race has a fraught relationship with the natural world. We have taken much more than it was ever meant to give. We’ve given ourselves rules, and placed ourselves in a society to maintain them, but stripped of these things we are left to reconcile our own addiction to convenience at the expense of others. The consequences of our progress have been monstrous. Walkabout comprehends these existential feelings, telling a story about survival deep within the Australian Outback, an area well-known for its majestic landscapes and oppressive conditions. Director Nicolas Roeg has a great affection for the wonders of this land, its fierce creatures and limitless space. Even its unforgiving heat, blistering and persistent, adds to its beauty. There’s an other worldly aspect to this land that feels so familiar and is still unlike any other place in the world.

A teenaged girl (Jenny Agutter) and her young brother (Luc Roeg) are left to fend for themselves in the Australian Outback after their father (John Meillon) commits suicide. The father’s behavior is not explained, his madness showing its first glimpse when he initially attempts to shoot his young son and the older sister is forced to hide them both behind a pile of rocks as the bullets ricochet. The father then sets their car on fire and shoots himself in the head. This moment, occurring within the first ten minutes and unfolding without warning or explanation is a shock to the system, a completely unexplainable event, particularly within the securities of our modern civilization. The brutality of it foreshadows their sudden reality: learning to survive within the arid landscape, hoping to find some place that can lead them back home.

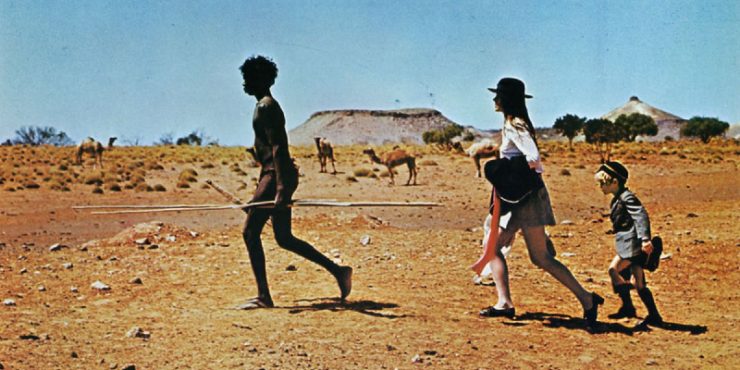

To their great luck, they meet a young Aboriginal boy (David Gulpilil) scouring the Outback on his own. The Aborigine is on his walkabout, an Aboriginal tradition precluding manhood in which a young Aboriginal boy is sent to live in the wild for as many as six months. The ritual is meant to spiritually connect the boy to the Earth and its many offerings, in preparation for adulthood. By the time he meets the young brother and sister, he is well prepared to help them find water, shelter and is not above hunting animals for them to eat. The brother, in particular, is fascinated by the Aborigine’s fierce but practical lifestyle. They develop a way to communicate despite not speaking each other’s language. The sister is more reticent, though she does find herself captivated by the Aborigine’s kindness and near-naked body.

Surviving the Outback with their new friend, the sister and brother become something close to comfortable in their new life, enjoying the simplicity of their nomadic routine. Roeg’s camera, which takes an almost Planet Earth-style approach to the Outback’s many creatures, imbues them with hallucinogenic intensity, juxtaposing their beauty with their ferocity. The film has obvious comments on the well-noted role racism, colonialism and displacement has played in Australian history. Seen through different eyes, both modern society and indigenous cultures have their fair share of barbarity. Walkabout manages to mostly stay away from racial tension to instead tell a story of discovery and innocence, about a transference between the two opposed ways of living.

Of course, the film is knowledgable enough to know that this transference will always benefit the colonizers and come at the expense of the indigenous. The same Darwinistic rules that make the Aboriginal boy better equipped to survive the extremities of the Outback, are the ones that dictate his people’s displacement at the hands of whites. Walkabout doesn’t dwell on this detail but neither does it ignore it. Its matter-of-fact approach goes hand-in-hand with its frank meditations on physical desire, with the sister’s curiosity of the Aborigine’s body soon transforming into the Aborigine’s romantic infatuation with the sister. Neither knows how to handle their feelings, or even what they mean, becoming frightened by their own urges while the young brother is oblivious to the tension.

Walkabout has a very good understanding of how arbitrary our society is and the silly ways in which we discern what is natural or unnatural savagery. Much like in his later film The Man Who Fell To Earth, Roeg shows a keen interest in the ways in which cultures react to things they are unfamiliar with. In that film, the human race becomes hostile toward David Bowie’s sculpted alien creature. Walkabout is much more tender, combining the innocence of the younger brother with the naivete of the Aboriginal boy, to overcome the sister’s world-weariness. Its contrasting of idyllic and macabre imagery creates a surreality that predicts the film’s eventual fall from grace. The heartbreak of its ending is softened by the wonder that precedes it, presuming a reality of coexistence that’s hard not to find endearing.

Directed by Nicolas Roeg