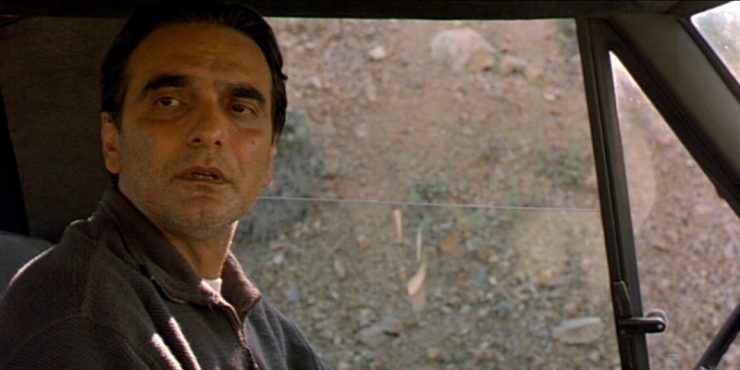

The words “In the name of God” open the film Taste of Cherry. It’s a modest but forceful title card that appears before we see any action. Not that there is a lot of action in the film. Most of it is spent inside of a Range Rover as it rides along dusty dirt roads outside Tehran. The driver is Mr. Badii (played beautifully by Homayoun Ershadi), a man in his middle age, dressed comfortably, neither rich nor poor. He is driving to find someone to help him complete a job, and so he searches the barren suburbs outside of the Tehran city center, passing laborers, soldiers and other working people. When he proposes work to these people, he often spins it as a favor he is doing for them, providing them with wages. As details are revealed, we see that it is Mr. Badii who most needs the favor, and if everything works correctly, it is the last favor he will ever ask for.

Badii wants to commit suicide. He refuses to say why. In one breath he says that the reasons don’t matter, but in another he says that he is unable to, as if discussing it will kill him on the spot. The one thing he is clear about is his pain and his unhappiness, which he sees as a bigger affront to Allah than the sin of suicide. This is an important detail: Badii is a pious, God-fearing man, and for that reason he would like to be buried appropriately after his suicide. This is the favor he needs; to be buried after his death in a grave he has already been prepared. There is a caveat: were this person to arrive and Badii is still alive, he will rise out of his grave and continue with his life. The hired person will still be paid the same amount.

Badii’s search is impatient and blunt. He approaches people on the street – in pay phones or in their work – and invites them to ride in his car. You can imagine how often people rebuff this invitation. Writer-director Abbas Kiarostami – one of the great Twentieth Century cinematic masters – is very hesitant to expand the film’s view outside of Badii’s car, staying within even as more action is heard off screen. On the few occasions we do venture outside, Kiarostami keeps the frame tight on Badii, isolating him from those outside of it, creating a crushing loneliness throughout the film. The director manages to make a populous city like Tehran seem desolate, like the center of an empty desert, which further cements Badii’s depression even if he refuses to speak it into existence.

Kiarostami’s camera is modest but sharp, trading austerity for clarity. His films are often about how supposed simple things can cloak complexity, and Taste of Cherry is a perfect example. There isn’t great logic to Badii’s actions; he proposes his job as if he is asking someone to help him change apartments. He thinks his offer is simple; an honest wage for a day’s work. The men he finds don’t see it that way. First there is a young soldier (Safar Ali Moradi), a shy Kurd who is in a hurry to get to the barracks for the night shift. Then there is an Afghani seminarian (Mir Hossein Noori) studying and working in Iran. Both men refuse Badii’s offer. For the soldier, he is frightened by the very offer, while the seminarian refuses for religious reasons. The seminarian tries to explain the sin of suicide, but Badii quickly becomes upset and decides not to listen.

In both instances, Badii appeals to their humanity, proclaiming his suffering and the righteousness of their action if they choose to fulfill it. He knows that his suicide will be a sin, but asks them to consider him as a human being. The soldier and seminarian, in refusing Badii, believe that they are doing the right thing and possibly even protecting him, but Taste of Cherry very cleverly shows their misdeed in declaiming the sin without assisting the sinner. They remove their own responsibility without taking any further action to prevent this sin from taking place. Whether Badii’s threat of suicide is legitimate or a cry for help is beside the point for Kiarostami. Taste of Cherry is an argument against religious reasoning that doesn’t include empathy.

The film’s third act is very powerful. Badii meets Mr. Bagheri, an Azeri taxidermist who agrees to the job because he needs the money to help his sick child. After accepting, he sees it as his duty to talk Badii out of it, to extol the virtues of life and prevent a tragic suicide. He recounts moments of depression in his own life, his own suicidal thoughts, and tells Badii of the moment he realized that life was worth living. Bagheri leaves Badii hoping that when he visits the grave the next morning, Badii will be alive. The conversation, short of convincing Badii, sets the meaning of the entire film. The only man who Badii listens to is the only man who chooses to participate in his suicide. After the refusals, it is Bagheri’s acceptance that ends up being the film’s most moral deed.

Kiarostami is much too shrewd a filmmaker to tell you what happens to Badii or to show if Bagheri’s anecdotes were effective or not. Even knowing the director’s penchant for experimentation and use of meta devices, the ending of Taste of Cherry will leave you stunned in its execution. Often one to toe the line between narrative and documentary, the film’s conclusion defies the limits of cinema, asking us to take the story’s themes and apply them quickly in a totally different context. It’s an ending that a much less talented director would not get away with, and one of the more delightful things I’ve seen in a long time.

Written and Directed by Abbas Kiarostami