The men in Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales are described as “fragile”. They lack a control over their feelings and emotions, specifically when they are in the company of women. Oftentimes, this lack of control projects itself as anger, resentment and jealousy. The source of their anger is usually another man – a much less “fragile” figure that gets in the way between our main character and the woman he is fantasizing about – and yet, the victim of the anger is almost always the women. The protagonists of these films behave within such a solipsistic existence that their emotional burdens take precedence over the feelings of others. In a way, that’s sort of the point: Rohmer is giving us an extreme intimacy with these men, so much so that we can even see when they are attempting to delude themselves. The division between their conscious and unconscious thought process is a more captivating tension than even their pursuit of women. It is also why their pursuits feel so obtuse.

The plots in all six films (two shorts, four features) follow a loose frame: a man in pursuit of one woman suddenly becomes infatuated with another. The two women are often opposites of one another; one being sensible and chaste, the other being spontaneous and impulsive. For the protagonist, the former represents the pure, pragmatic choice, while the latter presents an alluring distraction that threatens to overtake him. If things weren’t clear enough, Rohmer often makes his pure, ideal women blonde, while the adventurous, intimidating women are usually brunette.

Rohmer’s stringent, color-coded plot devices are an awkwardly engineered maze for his characters to work through. His men are tormented, torn between two women, as if each choice presents a wholly different existence. Their plight is extrapolated to existential proportions, a matter of life and death. Their pretensions allow them to use intellectual arguments on their own behalf, and their pedantic nature also lets them weaponize those arguments against women who do not bend to their specific needs. This is clearest in La collectionneuse (the fourth moral tale), where the frustrating Adrien (Patrick Bauchau) disguises his own lack of success in seducing the beautiful Haydée (Haydée Politoff), by telling himself that his own ideals wouldn’t have allowed him to seduce her in the first place.

Adrien is the most aggravating of the bunch within the Six Moral Tales, mostly because he has an inexhaustible ability to pontificate his righteousness in the face of his own behavior. He is, though, in no way unique within the series. The first moral tale, The Bakery Girl of Monceau, is a 23-minute short about a young student (Barbet Schroeder), who decides to introduce himself to a strange blonde beauty (Michele Girardon) he often notices walking amongst market streets. Once he’s decided to make his move, she has vanished, and as he passes the time waiting for her to reappear, he begins patronizing a small bakery where the teenaged shop girl (Claudine Sobrier) is obviously attracted to him. The young man in Monceau has a very precise focus on these women, often finding himself unable to consider both of them at the same time. When the bakery girl presents an opportunity for him the exorcise demons brought on by the blonde of his dreams, it’s alarming how quickly he changes course, pursuing the teenager (who herself is merely interested in flirting and becomes concerned when the young man becomes aggressive in his seduction) only to drop her at the end of the film when the blonde resurfaces.

Is the behavior by Adrien and the student ‘moral’? Both men rationalize their feelings and actions to justify themselves to themselves (justifying themselves to the women is not as big of a priority), and in both cases the rationalizations are often hiding the fact that their interest in these women is almost exclusively based on physical attributes. I’d guess that Rohmer is using the word ‘moral’ differently than most of us would. In fact, his own quotes about the films suggest they deal little with the more general idea of morality as much as they are constructed within the moralities that these men have set up for themselves. So, the films are not dealing with morality as a construct, nor do the tales themselves have a moral to impart to their audience. What we are left with, instead, is a “moral tale” in which men use their own self-justifying ideas of morality to create a force field against judgment from any outside person, as well as judgment from themselves. In keeping with the solipsism of the characters, self-judgment is what these men seem to fear most.

The second moral tale, Suzanne’s Career, is less than an hour long. Our protagonist here is Bertrand (Phillippe Beuzen), another timid student entranced by a woman named Suzanne (Catherine Sée). The twist in Suzanne’s Career is that Bertrand’s relationship with Suzanne is complicated by her relationship with Bertrand’s friend, Guillaume (Christian Charriere). Guillaume is a playboy, irresponsible and chauvinistic, uncaring of other people’s feelings. Bertrand is attracted to the danger in his friendship with him, and that attraction lends itself to Suzanne when she also becomes ensnared by it. Bertrand is courting the prettier, wiser Sophie (Diane Wilkinson), but his thoughts are preoccupied by Suzanne, whose relationship with Guillaume is quickly disintegrating. As Guillaume begins unleashing an emotional onslaught upon Suzanne (which includes infidelity and spending all of her money), Bertrand is resentful of the fact that she allows herself to be treated so poorly.

Bertrand’s thought process mirrors Adrien in La collectionneuse, who advises the alluring Haydée to begin an affair with his friend Daniel (Daniel Pommereulle), only to become envious that Daniel gets to partake in behavior that he himself would enjoy. Adrien and Bertrand both do all they can to belie their own feelings for women who don’t conform to their own moral construction of what a woman should be. Furthermore, they encourage these women to indulge in toxic relationships, as if to test their morality. In the end, Adrien and Bertrand sit back in solemn self-satisfaction when these women fail tests that they weren’t even aware that they were participating in.

In all of the Moral Tales, Rohmer is careful to include at least one scene where women are allowed to provide a perspective that puts a sharp pin into the tightly drawn balloon of these men’s worldviews. In Suzanne’s Career, it is Sophie who sets Bertrand straight about his feelings for Suzanne; namely, that any ill will should be focused on the despicable Guillaume, instead of the insecure Suzanne. Often, this feels like too little too late, as if Rohmer is inserting retroactively some attempt at objectivity. Sophie’s clear-headed analysis can hardly untangle Bertrand’s self-righteous reasoning against his friend’s girlfriend. Even the film’s title, somehow condemns Suzanne’s actions as her “career”, as if she has made a lifestyle out of being taken advantage of. This thought process, that women are merely characters within a fable meant to teach our protagonist a lesson, is held strong throughout the series.

The deeply analytical nature of Rohmer’s characters is an attempt to shield their seedier aspects, a superficial way to undo their sexist thoughts and actions. They believe in self-fulfillment but only when it comes to themselves, denying the women they covet the very freedom they’re so passionate about. The biggest exception to this within the Six Moral Tales is the third tale, My Night at Maud’s. The film stars Jean-Louis Trintignant, the only star actor to appear in any of the moral tales, and the only protagonist in the series whose moralities are built in a comprehensive way. Trintignant plays Jean-Louis, a self-serious engineer and ardent Catholic whose own search for the perfect partner is littered with disappointment. He wants to approach a blonde woman from his church (Marie-Christine Barrault), but then he meets Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorceé with a loose approach to being with men. Maud challenges him and his ideas, softens his stances, even convinces him to spend the night in her bed – albeit, he does so fully clothed. Nearly half the film is a conversation between Maud and Jean-Louis, which originally includes Jean-Louis’ friend Vidal (Antoine Vitez), but soon becomes just the two of them. Rohmer’s camera finally sits with one of its female characters for longer than a brief moment and actually listens. Consequently, Jean-Louis hears her as well. The eventual split between Jean-Louis and Maud – after all, he does end up with his blonde – is one of mutual benefit. Jean-Louis finds the Christian love he’s been looking for and Maud gets to continue her freedom, away from the confines of commitment. We even learn that the blonde, Françoise, has her own past, something that Jean-Louis has learned not to judge, thanks to the wisdom received from Maud.

Why does Jean-Louis feel so much different from the rest of the men in the Six Moral Tales? His logic isn’t any less self-deceptive than the rest of them. It could be as simple as the performance from Trintignant, the only truly reputable actor in the series – though he certainly didn’t have his reputation at the time. My answer is the addition of Catholicism, which brings with it a host of moral obligations and hypocrisies, gives My Night at Maud’s a purer interest in the ideas of morality than the rest of the series. Jean-Louis uses his religion the way Adrien uses intellectuality, but at least there is a true foundation to Jean-Louis’ stringent rules. Adrien’s high-minded beliefs turn out to be a house of cards. More than anything, it is Jean-Louis’ honest consideration of Maud and her life that separates him. Bertrand, Adrien and the student from Monceau either pretend to consider them, or contrive reasons why they never had to. Either way, their dishonesty to themselves does more harm to the women they are infatuated with than it ever does to their punctured egos.

Jean-Louis feels is not the only protagonist in the series to show empathy for women. So does Frédéric (Bernard Verley), from Love in the Afternoon, the sixth and final moral tale. Frédéric is a married Parisian man with two kids and a steady career (one of Afternoon’s charms is how Frédéric’s job is without definition, a stagnant office space of some generic capitalistic enterprise presented in bland beiges). Frédéric’s constant fantasies about strange women comes to a head with the arrival of Chloé (Zouzou). His self-deception is as severe as the rest of them, though he may be the only man in the series who is tormented not only by his own conflicting emotions, but also by the possible consequences facing the women of his life. Frédéric cannot help but be obsessed with Chloé, so much so that he’s compelled to frequently profess his commitment to his wife, Hélene (Françoise Verley), in an effort to throw people off the scent of his actual feelings.

What sets Frédéric most apart is his lack of rationalization. He understands that in choosing between Chloé and his wife, there is no choice that doesn’t cause pain. All the men within the Six Moral Tales fear of hurting their girlfriend, fiancé or wife, but Frédéric is the only one who shares that same fear about Chloé, the woman he is struck by. Love in the Afternoon is probably the second-best film in the series, after My Night at Maud’s, and the two are the only ones that take serious stock in the actual logic and difficulty behind committed long-term relationships. Jean-Louis believes in spiritual purity which causes him to spur Maud for Françoise, a shallow but at least understandable trade-off. Meanwhile, Frédéric has no moral hangups outside of his own conscience, which grips him in Afternoon’s final moments, when he abandons a naked, seductive Chloé to return to Hélene and make his marriage work. That Jean-Louis and Frédéric make a sacrifice of personal satisfaction in order to do right by the women they love is perhaps the only truly moral action these men take throughout this series.

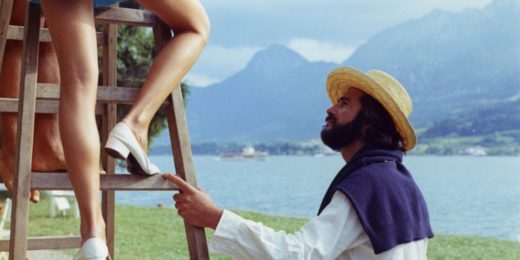

Which brings me to Claire’s Knee, the fifth moral tale and arguably the most popular film in the series. Claire’s Knee is a provocative film about an engaged diplomat named Jérôme (Jean-Claude Brialy) who takes a vacation in the South of France in the Summer before his wedding. Jérôme’s future wife is not with him, but he does have the company of his good friend, Aurora (Aurora Cornu), a novelist whose own failed love life inspires her to create a romantic drama for Jérôme. Aurora playfully suggests to Jérôme an affair with Laura (Béatrice Romand), the sixteen-year-old daughter of a neighboring vacationer. Laura has her own girlish crush on the much older Jérôme, but his interests lie more in Laura’s teenaged half sister, Claire (Laurence de Monaghan), another woman with long, golden hair and a shapely knee that Jérôme becomes absolutely obsessed with, and hopes to caress before his vacation is over.

Jérôme’s calculated seduction of Laura and then Claire fail in separate ways. Laura, after admitting she is “a little in love” with him, quickly cools before spending more time with a boy her age. Claire, on the other hand, has no interest, and in fact, has a boyfriend. Jérôme speaks guiltily with Aurora about his new attraction, though his language spends most of the focus on the knee, and not the rest of Claire’s bikini-clad body. I don’t know whether it’s Jérôme or Rohmer himself who feels the need to disguise lecherous behavior behind a preoccupation with a benign body part, but the game of bait-and-switch gives Claire’s Knee an even more insidious nature, as Jérôme waxes poetic about a knee, as opposed to the rest of her, which he so obviously wants. Another filter comes through Aurora, whom Jérôme also shares a relationship of surprising intimacy. Aurora continues her encouragement, caring little for the young girls, and more about Jérôme’s personal discoveries. Placing a woman in Aurora’s place gives Claire’s Knee and Rohmer another outlet to proclaim innocence – after all, how chauvinistic can it be if a woman suggests it?

The Six Moral Tales are a frustrating collection of films in which men (and the films about those men) perform elaborate calisthenics to give themselves the benefit of the doubt against mistreating women whose main crime is simply being attractive to them. This is most perpetrated by Claire’s Knee, which represents the worst of the 1970s sexualization of young girls. True, there isn’t the explicitness of American films like Taxi Driver and Night Moves – which in a way were about the dangers of this exploitation – but there is instead emotional manipulation, analytical excuse making. The young girls are swept up in Jérôme and Aurora’s experiment, and Jérôme uses the “game” as an excuse to make a move on them. For all his analytic posturing, his urges are physical, and he doesn’t seem to consider the innocence of Laura and Claire until after they have rebuffed him. Claire’s Knee’s popularity likely has to do with its controversial plot, but even in that regard, the film isn’t brave enough to discuss the more disturbing aspects of its story. Instead, like the men throughout the series, it scurries away in fear, unwilling to confront the actual issue, which is Jérôme’s entitlement, and furthermore, how that entitlement makes him predatorial toward young girls.

Consider the “prologue” of La collectionneuse, which introduces us to Adrien, Daniel and Haydée in three separate segments. The two men get short scenes of dialogue showing off their severely pretentious thoughts on art and relationships, while Haydée gets a wordless scene of her walking along the beach in a two-piece bathing suit. The camera moves up and down her body, and this is before Adrien has met her. This is Rohmer’s own assessment of her, which is only a breakdown of her physical parts. The prologue establishes how minds are valued in Adrien and Daniel, while Haydée’s value is simply her body. It’s actually refreshing to see it, compared to the rest of the series which avoids that direct kind of misogyny.

Now consider the sequence in My Night at Maud’s where Maud is given an opportunity, from the comfort of her own bed, to make the case for her own lifestyle to Jean-Louis, whom she hopes to have sex with. Maud has disrobed, but she is covered almost to her chin by bed sheets, and the camera is most focused on what she has to say. This is not only a more nuanced female character, but also one that the director obviously has more respect for. It’s hard to reconcile these two sequences, and that they were made by the same filmmaker. I wish it spoke to a variety throughout the Six Moral Tales, but it in fact speaks of an exception.

Rohmer may be most famous for being one of the founders of Cahiers du cinema, the groundbreaking film magazine which essentially set the intellectual foundation for the French New Wave. His films aren’t as beloved as Godard, Truffaut or Demy. In the Six Moral Tales, Rohmer gives us the worst parts of the New Wave (angry, pretentious men) while eschewing all of the cinematic innovation. His camera mostly sits aside, allowing actors space that they do nothing with, and with plots that lack so much action, you’d be surprised how little his filmmaking attempts to make up for it. And while other New Wave directors struggled with women as well, they at least gave their female characters point-of-view, outside of the male gaze. Rohmer certainly flies in the face of Agnes Varda, the movement’s most outspoken feminist, who often found herself having to undo the political damage of films like La collectionneuse which presented the Sexual Revolution as a playground for men to do whatever they wanted with any woman who came into their lives. The protagonist of Varda’s Vagabond, for instance, embraces the kind of spiritual freedom that Rohmer’s men opine about, though her actions would certainly have been dismissed by them. Perhaps it is because in Vagabond, Varda’s aimless woman shows no interest in men and their hangups, and is willing to sacrifice them to get that freedom.

I’d argue for the merits of My Night at Maud’s and Love in the Afternoon. Both films are emotionally fulfilling, arguing for their male protagonists while also letting the female characters have humanity. As a part of the Six Moral Tales, they seem to speak against the rest of the series’ hostility with communion between genders. La collectionneuse and Suzanne’s Career seem to predict the kind of dangerous incel behavior that has become so prevalent during the #MeToo movement, while Claire’s Knee seems to excuse the sort of predatory behavior that has made #MeToo such a movement to begin with. None of the films claim to be realistic portrayals of adult relationships. Rohmer is instead displaying complete immersion in the minds of these men, which comes at the expense of his own storytelling and bares the ugliest aspects of the male creative mind.