If you feel like the disparity between movies and television has shrunken, then Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series is a stunning example of it. The series is composed of five feature films, independent from one another in story and cast, but sharing a collected spirit of Black resistance against white supremacy in the UK. The first film, Mangrove, is a story of police prejudice that halfway through becomes a courtroom drama. Written by McQueen and Alastair Siddons, it’s based on the true story of the Mangrove Restaurant in Notting Hill, London. The Mangrove’s Black ownership and spicy cuisine are a beloved staple to Notting Hill’s West Indian population, who find the the restaurant’s menu and overall ambiance to be a welcome reminder of a home they left behind. For this exact reason, the Mangrove becomes a target of incessant police harassment.

McQueen has always been a political filmmaker, even if his movies never directly deal with government institutions the way that Mangrove does. His authority figures are often inhumane arbiters of destruction, who foist political turmoil on those who wish to avoid it and establishment systems exist to inflict pain and suffering on those who have little recourse to defend themselves. His most wide-known film, Best Picture winner 12 Years a Slave, is the most immediate example. The intimacy of his directing style and his tendency to leave shots lingering on difficult images forces reconciliation with what we’re seeing, and imposes the impact of oppression on the audience. It’s not that he doesn’t have faith in humanity, it’s just that he doesn’t see a path to redemption without the acceptance of great sin.

Those who criticize McQueen’s intense – perhaps pathological – focus on Black suffering will find little in Mangrove to dissuade them. In the film’s first half hour, the Mangrove and its owner, Frank Crichlow (an absolutely fantastic Shaun Parkes), are frequently raided, vandalized, and beaten by petty police officers who make it their mission to put the restaurant out of business. This charge is led by Police Constable Frank Pulley (Sam Spruell), whose virulent racism is hardly hidden and motivates his belief that the Mangrove is a breeding ground for drugs, prostitution and any other miscellaneous crimes he attributes to Black citizens. With only his hatred as evidence, Pulley begins a coordinated campaign of terror, entangling not only Frank but also his friends, children, and even the restaurant’s patrons.

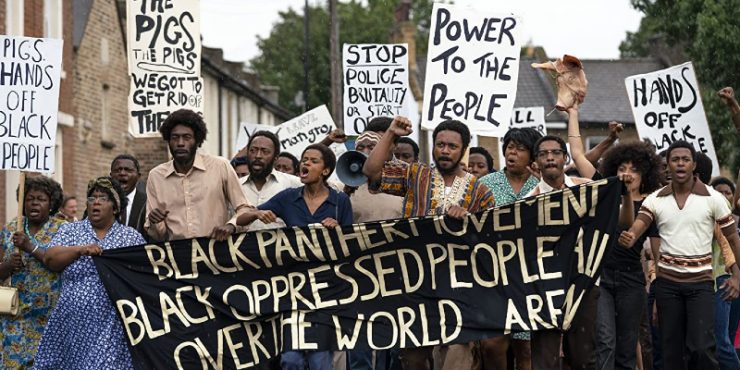

Frank’s situation catches the eye of both Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby) and Altheia Jones-LeCointe (Letitia Wright), two leading voices in the British Black Panther movement. Both regulars of the Mangrove, Darcus and Altheia also understand the symbolic importance of protecting Frank’s business against the white officers who wish to destroy it. They organize an anti-police protest that ends in punches thrown and several arrests. In the end, the Crown charges nine people, including Altheia, Darcus, and Frank, with starting a riot. In court, the “Mangrove Nine” take it upon themselves to not only defend themselves against the charges, but also to prove that Pulley and constables like him police their neighborhood in violent, prejudicial ways. The trial became the first acknowledgment in the UK of possible police racism.

The courtroom scenes of the Mangrove Nine may remind some of another recent release, Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7, a remarkably similar courtroom drama that was also based around the premise that the police’s response to demanded accountability is hostility and violence. Outside stating the obvious – that Sorkin and McQueen couldn’t be any more different as storytellers and filmmakers – the two films together present a rather stunning dichotomy of how to approach a subject. Sorkin is a much more polished writer, with an ear for feisty repartee and a preternatural talent for structure. McQueen is by far the more exciting director, whose distinct style and outsized formalism contrasts against the unhinged passions of his characters. More simply, Sorkin’s heroes were white and McQueen’s are black. And yet, both groups find themselves facing the Sisyphean task of simply asking the police to stop being violent, arguing for themselves in court rooms set up specifically to find them guilty.

I won’t argue much about whose interpretation of anti-establishment movements is more honest or effective, I’ll only say that one group among these two has a more storied history with police harassment. McQueen doesn’t have Sorkin’s ability to spin pretentious monologues into populist orations, and truth be told, McQueen’s workmanlike approach to the trial of the Mangrove Nine does sacrifice entertainment value, but that has always been the key to what McQueen is all about. To him, injustice does not have the occasional glimmer of hope. He does not stop to ponder the psychologies of those who choose to oppress. Even the victories in his stories seldom come out as triumphs. More often, they are sober reflections on the inhumanity one had to endure to get to that point. Mangrove makes great pains to display the toll that fighting for your own existence has on your spirit.

There are still four films to come from Small Axe (Amazon is releasing a new one for the next four Fridays). The project suggests an epic-ness that I wouldn’t have associated with McQueen. His early films were excellent but smacked of a sort of elitist independence and an unwillingness to produce anything mainstream. He’s managed to soften that stance while still possessing a commanding cinematic talent. He still enjoys the discomfort of his audiences, especially when that discomfort stems from an injustice that the audience may be complicit in. He will always challenge you. Small Axe shows that he’s willing to challenge you on a much larger scale than he had before.

Directed by Steve McQueen