Films as dark and subversive as Le bonheur are not usually so beautiful. Drenched in a rich, chromatic palette and played to the tune of twee renditions of Mozart (played by Jean-Michel Defaye), the third feature from Agnès Varda lives up to its title (Le bonheur means “happiness”), at least when it comes to its imagery. The story itself – of a married man’s nonchalant plan to love two women at the same time – is bleak and cynical, but Varda frames it through idyllic fantasies and media-created cliches. It is a deeply moral film that spends no time moralizing about its characters’ behaviors. Through the sheer will of the filmmaking, Varda removes our ability to truly judge these characters, whose main sin is consuming happiness.

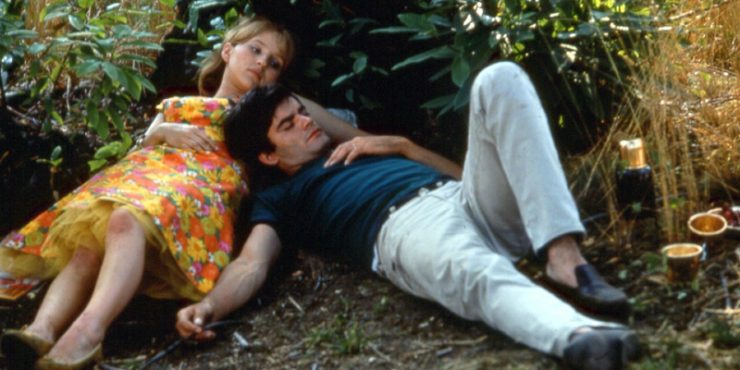

Varda cast famed Belgian actor Jean-Claude Drouot as François. François’s wife, Thérèse, is played by Drouot’s real-life wife, Claire Drouot. Their two children are played by their actual children, Olivier and Sandrine. From the start, Varda is beginning her clever game, where reality and fantasy blend, and the search for what is real can bring undue surprises. Le bonheur opens on a picnic in the woods, the young family trekking through large sunflower stalks before settling near a tree to have lunch and rest. It’s like paradise. François and Thérèse are happy, sublimely so. Their relationship is affectionate, physical and their attention to the children is superlative. François works as a carpenter in his brother’s shop and Thérèse is a dressmaker who works dutifully from home.

In the film’s opening moments, we’re privy to a wondrous display of contentment, an existence without issue or complaint. (A key early moment is when Varda’s camera is caught in the reflection of their car window, an omen that not everything may be what it seems.) When François meets a phone operator named Émilie (Marie-France Boyer), he doesn’t think twice before courting her. This moment, so contrary to everything we’d seen before it, is presented so frankly that it is difficult to digest. François tells Émilie that he loves her and visits her apartment where they make love. When at home, François does not give away any hints of his lurid affair. He’s still loving to his wife and kids, if not more so. He explains it simply to Émilie one night: he loves them both and it is only by chance that he met Thérèse first and started a family with her.

Both women make him happy, and the two happinesses stacked atop one another make him supremely joyful. François’s life, already a perfect picture of domestic bliss, is hardly disrupted by the addition of Émilie. So obsessed with his own happiness, François never considers his own selfishness. He ends up being just as forthright with Thérèse as he was with Émilie, stating plainly that his affair is one of love, passion mirrored by what he shares with his wife. In a moment of what I’m sure he would call generosity, he tells Thérèse that he will end the affair if she says so. After all, she is his wife. But like his mistress, François’s wife succumbs to his charms, prizing his happiness over her own.

From the audience, François’s behavior is solipsistic and borderline sociopathic. His philosophies on life and love are naïve and juvenile, guided by arbitrary interactions and happenstance. It’s not simply that he figures himself capable of loving to women simultaneously, but that he wishes for these two women to understand that this situation is in their best interests as well. He consumes and calls it sharing, without considering that his own fulfillment could come at the expense of someone else. Le bonheur‘s tragic ending – Thérèse is found drowned shortly after learning about Émilie – is grave, but Varda makes it yet another frivolity among others. François’s mourning of the mother of his kids is eased by his reserve love for Émilie.

Did Thérèse commit suicide? Varda is never explicit on this point, though it’s obvious that her life has become undone by François’s betrayal. That it happens so quickly after she buoyantly embraced his confession about Émilie adds to the discomfort. Once again, a character behaves so paradoxically to what we’ve seen previously. The drastic way in which her life ends is a stunner for François, who for the first time in the film is meant to confront the consequences of his actions. That confrontation is short, though, as he quickly moves on to Émilie and Le bonheur ends with the family resurrected with a new mother. The sequence, told mostly through a montage bursting with Mozart’s “Adagio and Fugue in C Minor”, is haunting in its directness. François again chooses his happiness, and his cruelty goes mostly unacknowledged.

Varda herself said that the film is meant to deconstruct clichés of domesticity. The lushness of its photography (cinematography by Claude Beausoleil & Jean Rabier) is meant to rub uncomfortably against the cynicism of its story. It’s a dreadful gift presented in whimsical packaging. François’s “honesty” is a shield for his misogynistic tendencies, and Varda thrashes it to bits. She exposes society’s views of romance as a complete fallacy meant only to please the very men who think little about ensnaring two women in an unseemly, unwanted ménage à trois. She scorns indulgence while showcasing it as a virtue. This monstrous conduct could only happen within a culture that willingly allows it.

The lack of militancy in Varda’s brand of feminist filmmaking should not be mistaken. Her visions of women are often individualistic and personal. She doesn’t often employ symbolism to be emblematic of more macro issues of sexism. Instead, she permeates all her narratives with femininity, and places those sexist constructs within them. Even Le bonheur, a film lead by the male Drouot, is explicitly feminine, both in style and substance. The result is shocking, an emotionally violent takedown of patriarchal politics, revealing the inhumanity incumbent within them. The very fact that Varda places Le bonheur inside such a utopian atmosphere makes the events unfolding feel almost like a horror film. And the horror is both our reality and the facade we choose to create around it.

Written and Directed by Agnès Varda