The restoration and re-release of Cane River in 2018 brought independent director Horace B. Jenkins’s film to many who had not heard of it before. Jenkins’s death in 1982 occurred shortly after the film was finished, which stunted the film’s ability to get a legitimate distribution deal. The film went unseen despite the clamoring of both Richard Pryor and Roger Ebert, who’d seen an advanced screening and championed its release. Cane River was a rarity of its time. Written, produced and directed by a Black filmmaker, financed by Black patrons, and casted entirely with Black actors, Cane River is completely isolated from black-white racial conflict so thoroughly associated with African Americans in cinema. The absence of whiteness allowed Jenkins to tell something even more radical: a story about Black love and education.

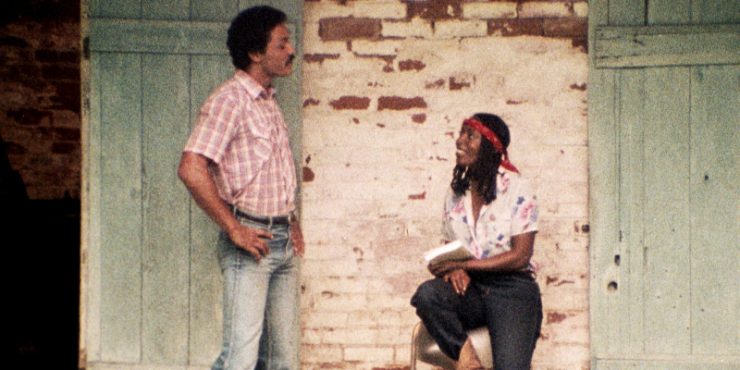

A documentarian by trade, Jenkins’s directorial technique is far from refined. His camera is much more interested in people than it is in visual storytelling, focusing on the characters, their organic behaviors and reactions. His lead actor, Richard Romain, was not a professional performer when he played his role, and he gave up acting soon after he’d finished filming. His main actress, Tômmye Myrick, is actually a director herself. The film’s coarse style makes the limitations of Jenkins’s direction readily apparent, but it also gives Jenkins a chance to tell a profound story. Set in rural Louisiana in towns with rich Black history, Jenkins traces the many tensions of between different Black cultures, and the class systems built upon the arbitrariness of location and ancestry.

Romain is Peter Metoyer, the chosen son in a proud Creole family that lives in Cane River, Louisiana. The Metoyer family descends from local Black aristocracy, wealthy landowners who gained power the previous century when African slaves mixed with French colonizers. Even during the horrors of slavery, the Metoyer ancestry were free Blacks who not only lived in the South, but ran a plantation and owned slaves. Their status, and their lighter skin tone, created a social distinction that has lasted well into the Twentieth Century, up to the moment Peter has decided to return to his hometown after turning down a chance to become a professional football player. A soulful, poetic soul, Peter has no interest in being a pro athlete, and wants to focus on becoming a writer. He thinks returning to his beloved hometown is the first step toward making that happen.

Peter’s excitement to return home is contrasted by Maria Mathis (Myrick), who can’t wait to flee town when she begins college in New Orleans at the end of the Summer. Her eagerness is quelled momentarily when she meets Peter on the very plantation that began the Metoyer fortune. Maria is reading a book about Black Creole families in Louisiana, so she is aware of his lineage and how prejudices have plagued African families like hers. Regardless, Maria and Peter fall for each other. She is enamored by his individuality, and he is fascinated by her strength and beauty. Maria’s mother (Carol Sutton) and brother (Ilunga Adell) don’t approve of the arrangement, and even Peter’s father (Lloyd La Cour) would rather his son avoid the hassle and drama. As Peter continues to learn the implications of their relationship, he chooses to have a better understanding about the economic dynamics between Black cultures in the American South.

The independent spirit rippling throughout Cane River has a very persuasive quality, overcoming Jenkins’s rough-and-ready execution. Soft lighting and an exuberant soundtrack gives the film an ethereal, almost mythological quality. The songs, by Leroy Glover (sung by Phillip Manuel and Anita Pichon), play over large portions of the film, working at times like a greek chorus and at other times like an intangible interpreter of the story’s many complex themes. Their polish goes a way toward pushing the film’s near utopian setting. Jenkins is aggressive in placing Peter and other Black characters into traditionally white American cowboy imagery, crafting a world in which Americana – equipped with cowboy hats and boots, as well as horseback riding – is covered in blackness.

Not that Cane River is attempting to be subversive. Its interests don’t lie in social arguments. Even its central conflict – landowning Creoles’ prejudice against oppressed African Americans – doesn’t consume the story, but instead paints the corners of the love story between Maria and Peter. The performances from Myrick and Romain are more memorable for their tender scenes of intimacy rather than for their stern disagreements. Jenkins puts more emphasis on spiritual fulfillment. Peter’s choice of poetry over football and Maria’s choice of a New Orleans college over her hometown speaks to both characters’ maturity and unwillingness to do what is expected of them. Their love is an extension of their search for actualization, which includes the uncomfortable details of their family histories.

Near the end, Maria and Peter agree to visit each other’s churches – his Catholic mass and her Baptist service. Both scenes, showcasing the sometimes extreme differences between the two denominations, gives each character a chance to share a piece of themselves that goes beyond religious belief. It is in fact an extension of their personhood and a display of their vulnerability. Cane River understands the rarity of these vulnerabilities within the canon of Black cinema, and leans into them. The sudden death of Jenkins disallowed us from seeing how these could have influenced Black filmmakers in the 80’s. This Twenty-First Century resurgence gives us all a chance to see something special, and understand how timeless Jenkins’s film really was.

Written, Produced and Directed by Horace B. Jenkins