How do you make a movie about this band? The very name, The Velvet Underground, suggests a hidden danger, an unquestioned coolness that can’t be put into words. I think that’s part of what draws in Todd Haynes, a profoundly talented director whose films often test the limits of gender and decency and explore the depths of eroticism and self-expression – much like the The Velvet Underground did with their songs. Any longtime fans of Haynes probably know of his affection for Lou Reed, the cantankerous but enticing Velvet Underground frontman, who became a glam rock icon after leaving the group (the character in Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine, Curt Wild, is partially based on Reed). In The Velvet Underground, Haynes is looking to paint a fuller portrait of the band as a whole, dominated by one man but possessing other parts.

Haynes has made films about musical artists before (though this is his first documentary), and each time he has shown himself much more interested in the more liminal spaces of creation than straight biography. The form and function of these films often match the musical style of the artist he’s profiling – Velvet Goldmine was as melodramatic and volatile as the glam rockers of the 70s, and I’m Not There was very much like Bob Dylan, a fascinating but mercurial puzzle where the inability to solve it was the point. The Velvet Underground replicates a lot of the New York City avant-garde scene where The Velvets were born. Talking head interviews are shot in an alluring film, both aging and aggrandizing the subjects. Split-screens are used to recreate Andy Warhol’s Factory style of perpetual imagery. The screeching feedback that The Velvets are so well known for is constantly bursting in your ear drums.

The documentary’s biggest treat is a 2018 interview with John Cale, the avant-garde musical artist who co-founded The Velvet Underground with Reed. A good portion of the film is dedicated to Cale’s steady journey through the experimental music scene in 1960’s New York City. Inspired in part by burgeoning artists like La Monte Young, Cale’s fascination with sustained tones (Young’s specialty), is the seedling that leads to The Velvet Underground’s exciting yet unnerving sound. Cale’s connection with Reed – a rebellious songwriter with more interest in doo-wop style rock n’ roll – becomes a perfect marriage of practical songwriting and musical experimentation. Despite Reed’s mainstream aspirations, his lyrics are dark journeys into drug abuse and logs of degrading sexual escapades. This eccentric fusion is discovered by Andy Warhol and the rest, as the say, is history.

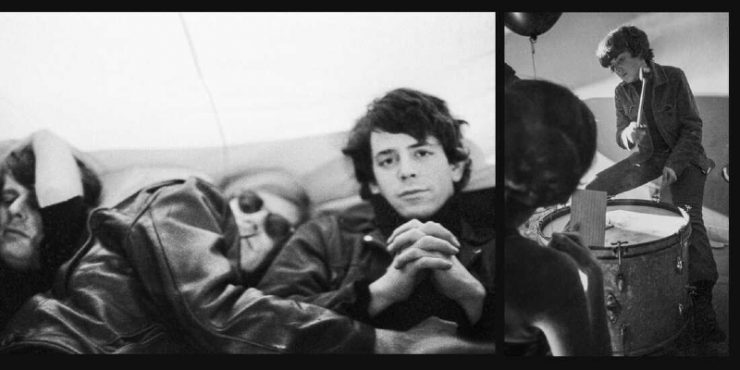

Drummer Moe Tucker (whose recent descent into Tea Party conspiracy theories was mercifully left out here) and guitarist Sterling Morrison join the group just in time to be the pet project of Pop Art icon Warhol, who makes The Velvet Underground the musical spectacle of New York. Most of the film is in fact about the creation and reaction to their first record The Velvet Underground and Nico. Said to be “produced” by Warhol, the album is their most shining achievement, with a deliciously provocative banana peel cover designed by Warhol himself (this alone probably earns him his dubious producer credit). Perhaps Warhol’s biggest addition to the group is the inclusion of the German singer Nico, whose deep, haunting baritone vocals added an iconic melancholy to some of their biggest songs.

Haynes’ filmography is in part a deconstruction of various genres, and The Velvet Underground is no different, frequently contrasting the usual beats of your average rock band documentary. There aren’t many big revelations in the film, and most Velvet Underground fans won’t find themselves having learned more than they already knew. I’m not really sure biography is where Haynes’ interests lie regardless, though the doc is surprisingly linear. He’s much closer to crafting a two-hour Velvet Underground song, a wandering experience through drug-fueled creation. There are various versions of “Heroin” played throughout the film, each one tinged with a different kind of desperation. Fueled by Reed’s restless bitterness, The Velvet Underground was always headed for implosion, and Haynes seeks to put you deep into that experience.

Past The Velvet Underground and Nico, the rest of the Velvet Underground’s short career is explored mostly as an extended downfall. White Light/White Heat‘s explosive defiance is a symbol of the building rift between Cale and Reed. Their third album, simply titled The Velvet Underground, is a softer turn, emerging from Cale’s departure; while their fourth and final album, Loaded, is the culmination of Reed’s total takeover, a deliberate attempt to court pop music success. I’m not sure I agree with this particular arc – that The Velvets’ separation from Warhol and then Cale was a signal of some pursuit of monetary gain at the expense of quality – but it is clear that their self-destruction was only a matter of time once the principals began departing.

I do wonder how interesting The Velvet Underground will be to non-fans, but I guess I could say the same thing about I’m Not There and Velvet Goldmine. Haynes is not a gatekeeper and his profiles are enthusiastically inclusionary, but he also cares not to catch people up on the inside jokes. The singular nature of The Velvet Underground is one of its strongpoints, unapologetic about its eccentricities much like Reed and The Velvet Underground themselves. I should confess here that The Velvet Underground are one of my own favorite bands. That, alongside my heavy admiration for Haynes, means I was predisposed to enjoy this, but I was still surprised by how immersive the experience was. Haynes takes a moment to explain to us the facade of Warhol’s factory, and the dangers it presented, especially to women. But in creating his own Factory film here, he reveals just how seductive and captivating it was. And the songs are fucking great too.

Directed by Todd Haynes