In a Jane Campion film, intimacy and brutality are often intertwined. The relationship between her characters is often a dance of passion and possession, with one often complimenting (and then disintegrating) the other. The Power of the Dog is a brooding slow burn, a story that spends its entirety unraveling methodically, until its final act where everything fits into place. Its narrative is one told almost exclusively through subtext, as fear and resentment display themselves in various ways through various people. It’s Campion’s first film in twelve years, since Bright Star in 2009, and it’s hard to think of a film more different in tone and effect. It is also one of the best films of the year.

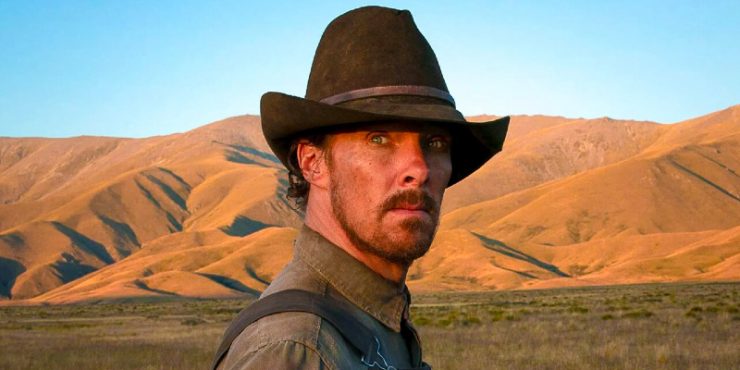

Benedict Cumberbatch plays Phil Burbank, a snarling cowboy who owns a ranching business with his brother George (Jesse Plemons) in the early Twentieth Century. Their business has allowed them to build a grand home in the middle of arid Montana, where the sprawling faraway mountains create a breathtaking landscape against the big sky. Of the two of them, George purports himself more like a contemporary businessman, with pressed suits and a fresh shave. Phil has still not taken to civilization, bypassing the in-house bathtub for mud baths in the local river. His face and hands are usually stained by the day’s work, his hair falling in greasy clumps in front of his face. Phil’s hostility with George’s ambling shift toward domesticity is fierce. More often than not, Phil will refer to George as “Fatso” instead of his actual name.

From the beginning there is an air of mystery between the brothers. Their history of success doesn’t totally vibe with their current bitterness, and Phil’s ferocity – his reputation for brilliance seems to have whittled itself down to pure anger – creates a perpetual tension. Things get worse when George marries Rose (Kirsten Dunst), a widow and tavern owner with an eccentric teenaged son named Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee). Rose is a melancholy sort, sensitive to reproach and anyone who attacks Peter’s lisp or gangly figure. When she moves into the Burbank home, she has immediate distress, as Phil wastes no time making her feel unwelcome. For Phil, Rose is a symbol of the rising tide against his preferred ranching life. For Rose, Phil is the complete embodiment of evil.

Campion’s script (adapted from the novel by Thomas Savage), keeps things opaque throughout. Motivations are unclear and actions unpredictable. Things take a turn when Phil decides to befriend Peter, a move that not only brings Rose skepticism, but the audience as well. As presented, Phil is a man capable of anything. His complete disdain for those around him is unlike anything I’ve seen since Daniel Plainview, and that’s not the only thing that Power of the Dog has in common with There Will Be Blood. As Phil and Peter begin to bond, it’s hard to tell who is setting up who, where the power dynamic lies. Campion keeps you guessing until the film’s final moments, where the smallest of expressions reveals an overarching plan brewing just under our noses.

As the story whirls away, Campion crafts beautifully lush landscape shots, framing the characters against the vast American West, both brimming with promise and forbidding in its cruelty (despite its American locale, it was shot in Campion’s native New Zealand). With cinematographer Ari Wegner, Campion constructs astonishing set pieces, giving us a clue of what Phil and Rose are thinking but dare not say. A score composed by Jonny Greenwood (another similarity to There Will Be Blood) unsettles with morose tones and cacophonous strings, further entangling the film in foreboding. Every moment in Power of the Dog seems aimed to create imbalance and discomfort, to keep you guessing. It’s a surprisingly seductive filmmaking strategy, as you’re sucked into this combustable family.

The ensemble, led by the amazing Cumberbatch, is incredible to behold. Phil is unwaveringly combative among others, yet strikingly vulnerable when alone, himself trapped in a prison of his own making. This is a difficult disparity to manage but Cumberbatch does so brilliantly, faithfully creating the monster and its origins. Vague references to a since-deceased mentor named Bronco Henry looms large in his life, and as the film progresses, the nature of that relationship becomes more complicated, perhaps the source of his self-loathing. As Rose, Dunst is also given the unenviable task of expressing everything and saying nothing. Her despair, which manifests itself in heavy drinking, corrodes her soul. If Phil is willing to put himself through agony, he is more than willing to bring her with him.

The Power of the Dog‘s brilliance lies in the totality of Campion’s control. We’ve known that she’s a masterful filmmaker for decades, but Dog is a phenomenal example of extreme precision. Nothing is explicitly said in the film, everything is hinted, hidden within small details sprinkled throughout. The battle between Phil and Rose is one between two people unable to say how they truly feel, and that presents itself in barbaric behavior and crippling depression. As you approach the film’s stunning conclusion, you realize that the suffocating suspense was all part of the endgame, a rough-and-ready journey through ferocity to find grace. It’s been such a long time since a director held me so tenuously in their hands this way, where my trust in them was so handsomely paid off. It’s a rare thing to see.

Written for the Screen and Directed by Jane Campion