In a year filled with auteurs making their autobiographical films, Bardo certainly stands out. If James Gray’s Armageddon Time is a New Hollywood-style exploration of the troubled domestic ethics within the Reagan era and Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans is a wide-eyed examination of how the personal and the magical intermingle, then Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s latest film is a kaleidoscopic, Fellini-esque deep dive into the world of mortality, Mexican history, and the humiliations that come with being an immigrant in America. The film’s ridiculous indulgence is a feat in and of itself, an operatic shrine to ego unlike anything you’ve ever seen. And yet, Bardo won me over more than any Iñárritu film previous to it, and that is perhaps because it is so outright with its aching sincerity and moralistic dialogue. The visual style is so striking and audacious that it almost needs a narrative as emotionally convoluted as this.

His previous two films, Birdman and The Revenant, were twitchy exercises where the virtuoso director flexed his camera skills to the detriment of coherence. I found Birdman to be a superbly-acted, funny-enough satire of artistic vanity, but The Revenant was a movie that aimed for cerebral but landed squarely in blunt pretension. Both won him Oscars for Best Director, but his reputation for heavy-handedness still managed to supersede any standing he had as a technical proficient. The least liked of the industry-crowned Three Amigos, the meandering nature of his scripts keeps him from attaining the genius moniker of Alfonso Cuarón, and his penchant for miserable-ism means he falls well short of the jovial popularity of Guillermo Del Toro. The credit he gets for his ample talent is often expressed through gritted teeth. Making a film as personal as Bardo unlocked something in Iñárritu for me: he’s not the severe figure his films might suggest, but a storyteller searching for a home.

This is Iñárritu’s first Spanish-language film since 2010’s Biutiful, a movie so depressing it almost felt like sport. That movie was saved by a great performance from Javier Bardem, but it also cemented Iñárritu’s reputation as an it-only-gets-worse doom monger. Birdman was a welcome change of pace, and if it proved anything to me, it’s that he does indeed have a sense of humor, but even that film requires its stellar ensemble to search out the laughs in a pretty didactic script. Bardo, a movie that never met a cinematic flourish it didn’t execute, is the first of his movies that really captures that middle ground. Its humor is spiked with bitterness, but its sorrow is faded with cruel ironies that are often enough to make you grin. In the film’s lead role is Daniel Giménez Cacho, the Mexican actor whose performance in 2017’s Zama is some of the best craftwork you’ll ever see. His tenor in Bardo is much looser; less tightly wound and more recklessly unspooled. He is Iñárritu’s stand-in, wildly expressing the rambling inner monologues of a man unmoored from reality.

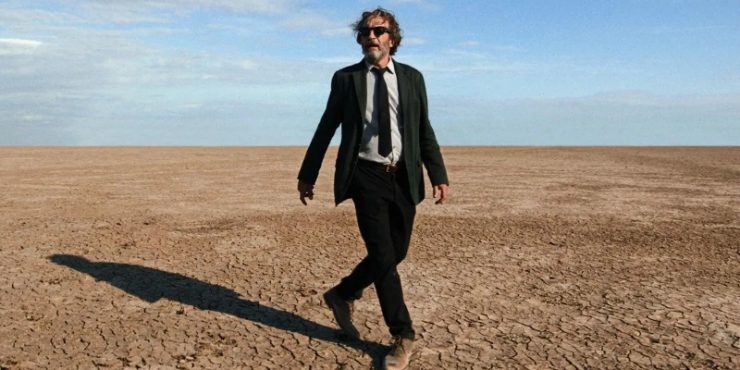

Giménez Cacho plays Silverio Gama, a journalist turned documentarian whose success has taken him from grunt work in Mexico to an upper class lifestyle in Los Angeles. His award-winning films have granted him the ability to trade integrity for status and glamour. When he’s announced as the winner of a prestigious international award, Silverio decides to go back to Mexico, visiting old friends and family, re-encountering old resentments and past traumas. His wife, Lucía (Griselda Siciliani), tolerates his ever-shifting moods and manages his fluctuating schedule. His children (Ximena Lamadrid and Iker Sanchez Solano) are less patient, quick to frustration when Silverio gets started on his many self-righteous monologues. He brought them to America to give them a better life, free of the violence and corruption that has permeated Mexico, but he’s disappointed by how much was lost in transition, creating a perpetual unspoken tension between them. That tension is a residual for the substantial loathing Silverio also has for himself.

His re-emergence in Mexico welcomes several angry confrontations and a handful of bittersweet reunions. Many ex-colleagues and long-unseen relatives are quick to kid him about his expatriation. He sees his lonely mother (Luz Jiménez), addled with dementia, and is visited by the affectionate ghost of his father (Luis Courturier), who tries to calm his anxieties. A former friend and television host (Franciso Rubio) approaches with a smile though he can’t wait to get his moment to cut him down to size. Getting it from all sides, Silverio turns inwards but has little success finding peace there either. Bardo‘s persistent bouts of surrealism give Iñárritu and cinematographer Darius Khondji a wealth of opportunity to create wondrous set pieces flowing with color, and extending into the long takes that have become Iñárritu’s calling card. His expansive shot lengths, ever boastful, find proper context here, as it precisely imitates the journey through Silverio’s crumbling mind.

Early in the film, Silverio meets with the American ambassador to Mexico (Jay O. Sanders), who flatters but is fishing for the contents of Silverio’s acceptance speech. There is fear that Silverio may take the opportunity to express controversial (possibly un-American) opinions. Unbeknowst to the ambassador, Silverio hasn’t written his speech yet but he does little to asuage his apprehension. Silverio has found fame and fortune in America, but he doesn’t miss any chance to needle them about their colonial sins of the past. The scene mirrors a similar, but much more phantasmagoric sequence later in the movie, where Silverio climbs a mountain made of the corpses of Indigenous Americans, only to have a conversation atop of it with the contemplative specter of Hernán Cortes. The two scenes, both analagous and paradoxical, allow Silverio to speechify about the injustices that have led not only to the ruthless killings of so many native Mexicans, but also his own mental disintegration. In Bardo, the personal and the universal are intertwined.

So you see that Bardo is not a film that follows rules. The physics of a scene will morph into whatever it needs to be to put its thematic point across. Despite it all, this is not a difficult film to understand, and if you’re willing to sit through it (there were a few walkouts in my screening at least), you’ll see that its symbolism is pretty straightforward after all. The film’s subtitle, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, is both an honest account of what you’re about to see and also a winking hedge in case anybody try to box it into the genre of memoir. This is the first Iñárritu film that I found endearing and I found it tragically so, a spiraling narrative that risks being maddening to get across its themes of grief and displacement. As obtuse as this may have seemed to some, this to me felt like the kind of unwrangled artistic vision that we should be clamoring for more of. Sparing no effort to reflect the endless conflict within his soul (and translated so beautifully in Giménez Cacho’s performance), Bardo is an astonishing feat.

Directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu