Some people never get a real chance. Some are chewed up by life from the start, a tragic victim of circumstance and chance. Joaquin Phoenix’s Joe in You Were Never Really Here is one of those people. He’s one of the few who has made it well into adulthood without a complete psychic breakdown (though I guess that could be debated). That doesn’t mean that all is well. Joe is the center of Lynne Ramsay’s latest film: a bleak, shockingly violent portrait of an unhinged man’s quest to put himself together for once. Using mostly a hammer and a surprisingly intuitive feel for combat, Joe acts out in furious fits of violence, doing dirty work for people who don’t like getting blood on their clothes. When he’s hired by a senator to rescue a teenaged girl from a seedy prostitution ring, he treats it as business as usual. And as usual, a lot of people end up hurt.

Joe lives with his mother (Judith Roberts) in New York City, watching after her and taking care of her in her advanced age. The specifics of Joe’s profession are obscured, left with little explanation, but most directly, he works for a man named John (John Doman) who pays him to rescue young girls out of sex trafficking. Joe seems to be quite good at his job, though he doesn’t seem to show any outward appreciation for it and his payment for it seems closer to adequate than plentiful. The job seems to satisfy a stinging urge, both to protect and also to do harm. Joe is plagued by PTSD flashbacks of his time in the Middle East as a combat soldier, and his time spent as an FBI agent. The film also shows a troubled childhood, tormented by a faceless, tyrannical father with abusive tendencies. Joe wants to save children, but he also really, really wants to hurt adults.

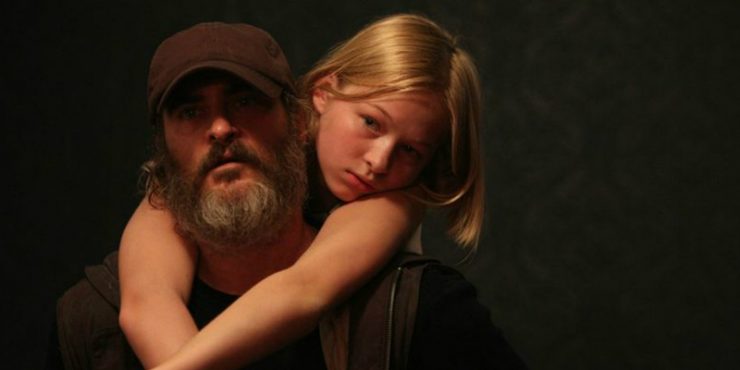

Phoenix, a formerly sardonic actor with a wicked charm, has now become a master of the brooding outcast, with an uncanny ability to portray anguish and trauma with very little more than the movements in his face and eyes. The rest of his body he wields like a blunt instrument, his torso covered in scars of various origins, his long hair and beard spread out wild and mangy. Phoenix has become a kind of go-to actor for traveling down and deep into the heart of darkness. He’s unafraid of what he’s able to find within the character and within himself. Like his career-defining work in The Master, his performance in You Were Never Really Here will disturb you just with its mere presence. Phoenix won the Best Actor actor award at the Cannes Film Festival last year, where they’re more responsive to these kinds of harrowing, internalized performances. One can only hope he gets the same attention in the States.

In her first feature since 2011’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, writer-director Lynne Ramsay crafts an unflinchingly brutal film, a movie so fully entrenched within a mind filled with horrors past and present. Since its premiere at Cannes, many have drawn parallels to Martin Scorsese’s 1976 masterpiece, Taxi Driver, which makes sense. Both films involve a troubled man saving an underaged girl from prostitution, both show a stinging distrust of the local New York government, both feature unique scores that swing violently from melodic to cacophonous (Here‘s score is by the brilliant Jonny Greenwood). With Taxi Driver – which was probably more of screenwriter Paul Schrader’s movie than a Scorsese movie – there was a direct anger with New York and its ecosystem. You Were Never Really Here is a man’s singular focus. His most violent behavior comes at the expense of others. His most hateful thoughts, he saves for himself.

You Were Never Really Here feels much more visceral and effective than other recent gritty violent pictures. Its relationship to its bloodiest sequences is both blunt and modest, cutting away at moments of impact, letting us hear instead of see, lingering over the aftermath as opposed to seeing the bullets, knives and hammers fly. It’s a Hitchcockian device that truly highlights the emotional and psychological pain radiating through multiple characters within the narrative. Ekaterina Samsonov plays Nina, the young girl Joe is tasked with saving before things go horribly wrong. She’s no Jodie Foster, but the pain of her existence – her role as a sexual plaything between several abhorrent men – is readily available on her expressionless face. Ramsay, an old hand at the harrowing drama, shows her best work here, a climactic showcase of suffering and self-loathing, a plethora of bad feelings. And yet, the film has the audacity to be hopeful. The film’s final sequence, which I won’t reveal here, is unquestionably brilliant, equal parts shocking, funny and bloody. It’s the only ending that could have tied this unwavering narrative together, and it does so with a flourish.

Written for the Screen and Directed by Lynne Ramsay