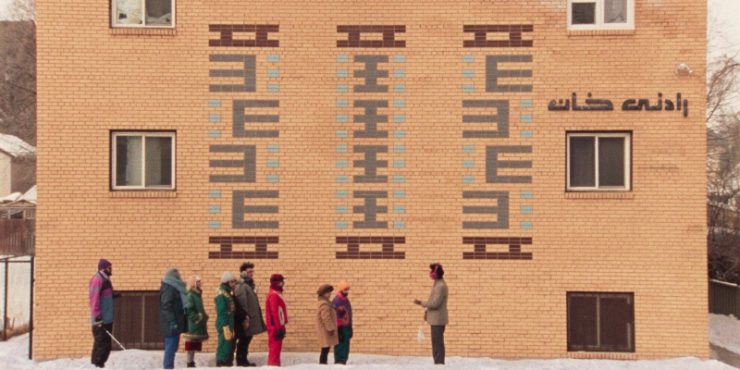

Taking place “somewhere between Tehran and Winnipeg”, Matthew Rankin’s Universal Language is a piercing, absurdist comedy in the tradition of Roy Andersson by way of Abbas Kiarostami. The Winnipeg of the film is filled with beige, Twentieth Century architecture, and all the signs are in Farsi. It’s population much more resembles the people of Iran than Canada, speaking Farsi with the occasional dabbling in French. Outside of Andersson and Kiarostami, allusions abound to the likes of Wes Anderson, Guy Madden, Agnès Varda, Hal Ashby, etc. Written with Iranian artists Ila Firouzabadi and Pirouz Nemati, Rankin creates a singular vision in his sea of homage, crafting sequences of visual flair and hilarious eccentricity. It’s important that Universal Language manages to be incredibly funny, as it’s aggressive style can sometimes be hard to parse otherwise.

Two young sisters, Negin (Rojina Esmaeili) and Nazgol (Saba Vahedyousefi), go to class in a deranged French immersion school, where young children are taught French grammar and pronunciation. Their temperamental teacher (Mani Soleymanlou) refuses to continue lessons for the children until one of the students retrieves his lost glasses. The student claims they were stolen by a turkey. When the sisters find money frozen under the snow, they start planning on how to get it out, so they can give it to their classmate, he can buy a new pair, and school can continue. They briefly collaborate with a meandering tour guide, Massoud (Nemati), whose tours through this modified version of Winnipeg includes long monologues about seemingly unimportant parking lots and thirty-minute moments of silence. Massoud gives them a tip about who can help them get the money out of the ice, but the sisters fear that if they leave, Massoud may take the money for himself.

Rankin himself plays a character named Matthew, a Winnipegger working a soulless job within the Quebecois bureaucracy. A sequence where he tells his boss that he’s quitting really sets up the film’s desert-dry humor and surreal atmosphere. He wishes to return home to reconnect with his estranged mother, but even getting back proves difficult. Every person he consults with meets him with hostility, and more than one of them insists that Winnipeg is a city in Alberta, not Manitoba. When he calls his mother’s house, a strange man answers the phone. Your mother no longer lives here, the voice explains, meet me at Tim Horton’s and I can explain. So Matthew traverses this altered reality, buys flowers for his late father’s grave, has a run-in with Negin and Nazgol, and catches glimpses of Massoud’s bizarre tours. He appears unaffected by being the only white Canadian in town, but we can see that something is amiss. Home isn’t what it used to be.

The script links these various tales, sometimes through random circumstance and sometimes through some unexplained providence. The story moves in directions impossible to foresee and gives us surprising moments of tenderness within a vast canvas of farce. That homage is such an important part of the movie’s effect is not a demerit. Rankin, Firouzabadi, and Nemati have a true love and deep understanding of these traditions of cinematic storytelling. There are plenty of moments in Universal Language that I could not explain, but the filmmaking is so precise and the comedy so dense that it’s hard not to be impressed by what Rankin achieves. The themes are legion and not always easy to pin down. If someone accused this film of being over-stylized, a defense would be difficult, but those traditions it shows affection for are inspired by community, and this is a very welcoming film.

I saw this movie in the first week of November 2024. My first time in a movie theater since the re-election of Donald Trump, and all the baggage that that brought with it. Now, it’s February, and the second Trump administration is formally under way. It makes one more appreciative of Rankin’s vision of community; imperfect but warm-hearted, solidarity tinged with melancholy. It’s vision of the world is different enough to help you forget how we live today, but that doesn’t mean Universal Language is blind to the world’s ills. These characters are spirited, but still motivated by unnecessary desperation. Children forced to mine money from ice to continue their education, one man met with indifference as he tries to share his love of his home, while another man tries to reconnect with his past, only to find that past far out of his reach. It’s some heavy stuff that Rankin manages with a light touch, crafting Universal Language into one of the more original moviegoing experiences I’ve had in a long time.

Directed by Matthew Rankin