Between this movie, Megalopolis, and Sofia Coppola schilling mass-produced stationery as a fashion accessory, 2024 wasn’t exactly a banner year for the Coppola brand, in terms of quality. The Last Showgirl did all the work it needed to do in casting Pamela Anderson in the lead role, but I wish director Gia Copppola had done even a little bit more to make this film something special. As it stands, it’s gritty indie aesthetic and my-glory-days-are-behind-me narrative arc stretches itself thin in an attempt to be Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler. It ends up feeling more like parody than homage. Anderson is an actress whose career is mostly defined by the misogyny used to attack her throughout the nineties. This industry owes her a million apologies. Instead, they’re patronizing her with award nominations this movie doesn’t deserve.

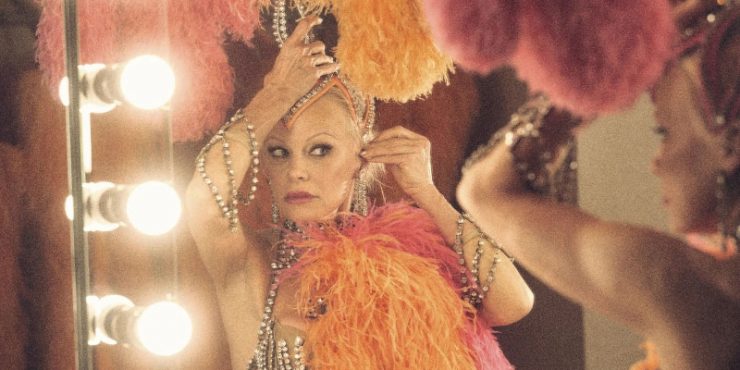

Anderson plays Shelly, a Vegas dancer at Le Razzle Dazzle, a decades-long show on the strip that promises glamour, elegance, and (most importantly) topless women. Shelly’s been the main attraction for a large portion of the show’s legendary run, but after thirty-eight years, it’s coming to a close, replaced by a burlesque circus. The veteran performer needs to figure out what’s next in her life. She reaches out to her estranged daughter, Hannah (Billie Lourd), but prospects there seem slim. She considers living with Eddie (Dave Bautista, wearing an incredible wig), Razzle Dazzle’s producer whom she shares a complicated history. The younger dancers at Razzle Dazzle (Kiernan Shipka, Brenda Song) are disillusioned by the situation. They know they’re selling sex, while Shelly insists that they’re selling enchantment.

Annette (Jamie Lee Curtis) is a former Razzle Dazzle dancer turned casino cocktail waitress. Her gambling issues, alcohol dependency, and generally volatile demeanor have caused her life to spiral. Annette is the nightmare scenario that Shelly wants to avoid, but that proves difficult since Shelly can’t break out of the past, where her peak allowed her to travel the world and be treated like a movie star. The film is written by Kate Gersten, and it’s adapted from her own unproduced play. The script struggles so mightily with forward progression that it relies exclusively on contrivances to keep the story going. One wishes Gersten and Coppola instead opted for a looser narrative, one that trusted its characters and its actors to keep us interested, and one that more appropriately matches the verite style its looking to achieve.

Gia Coppola and cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw spend a good amount of the movie in extreme close-up, shooting scenes in such soft focus that the film is basically out of focus a good amount of time. One struggles to understand the reasoning for it beyond a desperate grasp for edginess, some cheap recreation of 70’s pastiche. It’s indicative of the film’s major problem: all of its choices – and, subsequently, all of the characters’ choices – feel dishonest, like it’s forcing itself to be a movie that doesn’t exist. If you want the burnt ends aesthetic of Andrea Arnold or Alex Ross Perry, one must understand that a big part of visual storytelling is the story. There just doesn’t seem to be a whole lot of thought put into this one, and one wonders if a filmmaker not named Coppola (or Spielberg or Scorsese) would even have gotten the opportunity to make it.

The movie is sometimes at odds with Shelly’s profession, sometimes in awe of it. Sometimes it respects her glass-half-full demeanor, sometimes she’s exposed as naive, delusional. The performance from Kiernan Shipka is the film’s lone bright spot. She plays Jodie, a teenaged runaway caught between the romantic protestations of Shelly and the it’s-a-living realism of nearly all of the show’s other girls. Shipka – known mostly as the precocious Sally Draper on Mad Men – has been collecting very good supporting performances in a wide array of movies in the last few years. Last year, her small parts in Twisters and Longlegs made indelible impressions. One hopes that a smart filmmaker is able to take advantage of her adroit humor and grounded vulnerability sometime soon.

Pamela Anderson received first a Golden Globe nomination for this and, more recently, a SAG nomination. The fact that Anderson was starring in a self-reflexive drama paralleling her own harshly-judged career was enough of a hook for most people to buy this movie’s off-screen narrative. Anderson is good in this movie – sometimes quite good – but the suggestion that she should be recognized over the likes of Marianne Jean-Baptiste in Hard Truths or Julianne Nicholson in Janet Planet is ridiculous to the point of being offensive. It’s not her fault. I’m glad she got this role, and I’m glad she’s getting a chance to redefine herself, but that Hollywood thinks they can make up for mistreatment by treating this performance and this film as anything more than a mediocrity is a symptom of a much bigger problem.

Directed by Gia Coppola