Josh Safdie is a stylist of the highest order. Until his latest film, Marty Supreme, he shared all directing credit with his brother Benny, and in less than a decade they did a great job of creating the undeniable feeling of watching a “Safdie brothers movie”. It meant that you’d be watching an unflinching New York movie that paid homage to popular American films of the 1970s while containing a contemporary level of extremity. Sidney Lumet with a touch of Saw. The brothers, along with distributor A24 affected a style that was unique to themselves. Between the two of them, it was always Josh that seemed to be the more auteurist-minded. Benny’s main interest seemed to lie in acting – and he’s managed to get himself roles in films by some of the greatest film directors alive. So it makes sense that Josh going it alone with Marty feels in no way like a partial Safdie experience, but a more fully realized one.

The movie stars Timothée Chalamet, the baby-faced movie star of his generation who, at just thirty, already feels overdue for an Academy Award. Marty Supreme feels like the film built to do it. I don’t mean that Safdie’s film or Chalamet’s performance is some kind of awards bait, but that the performance at the center of the film is such an undeniable statement of talent that needs only an Oscar to further cement it. De Niro in Raging Bull type stuff. It’s nice to talk about a Best Actor contender through the lens of its quality and not through its cultural narrative. Cillian Murphy set a new standard for this award two years ago. It might actually be a meritocracy after all.

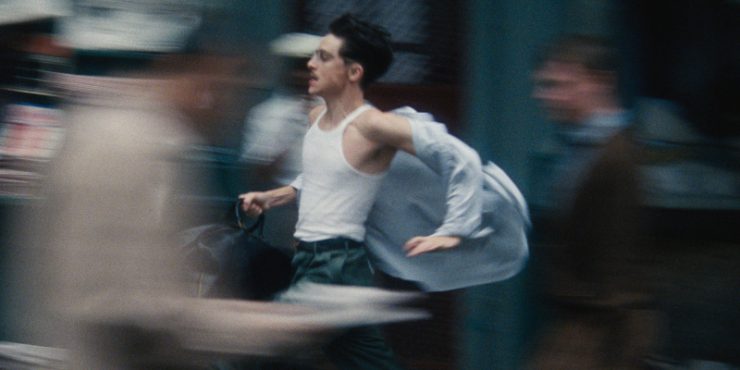

Chalamet plays Marty Mauser, a preternaturally talented and clinically arrogant table tennis player with grand dreams of being one of the most iconic athletes of his generation. His skill is undeniable but his methods of self-promotion border on the sociopathic. That may be in part due to his origins. Marty is living in the slums of the Lower East Side in post-war New York City. Less than a decade removed from the Holocaust, Marty doesn’t shy away from his Jewish heritage, and in fact rubs it in the face of friends and opponents alike. To make ends meet, Marty works for his uncle in a shoe store, but he’s very transparent about his lack of interest in retail. This is all a way to raise money for a trip to the world championships in London, where he hopes to gain the international recognition (and financial compensation) he believes he deserves.

This is very much to the chagrin of his mother, Rebecca (Fran Drescher), who wishes for Marty to be close and is not above using manipulation to convince him to stay home. Marty’s withering affection for Rebecca notwithstanding, he’s completely immune to her attempts to appeal to his sensitive nature. In fact, he’s immune to anyone claiming that there is any personal obligation more important than his quest for ping pong greatness. There’s also Rachel (Odessa A’Zion), a neighbor and childhood friend with whom Marty is having an illicit affair with. Rachel’s marriage to the temperamental Ira (Emory Cohen) gives Marty little resistance, and Marty reaching for what he wants without much thought given to consequence is a running theme throughout Marty’s hectic life. When Rachel reveals to Marty that she’s pregnant with his child, he’s less skeptical of his paternity as he is frank about how little it will dissuade his life’s plans.

So it’s quite the blow to Marty’s substantial ego when he loses in the world championships final to the unassuming Koto Endo (Koto Kawaguchi), a Japanese savant with a unique serving style. From that loss, Marty decrees that he will return to the next year’s world championships (hosted in Koto’s native Tokyo) and defeat the man who proved him mortal in front of everyone. But first, he has to get there, which includes raising money for air travel and lodgings. The fact that Marty burned bridges with the tournament’s manager (played with perfect iciness by novelist Pico Iyer) doesn’t help matters. Flashing forward a year and Marty is hardly close to amassing the money to go, which leads him on a chaotic, days-long journey to finance his return to glory.

Marty has numerous options, but those options are often undermined by his caustic, often rude demeanor. Marty strives where he should grovel, refusing to apologize for his behavior, so sure he is that his talent will overcome it. He’s often mortgaging present debts against tournament winnings that have yet to happen. The shoe store-owner uncle (played by Larry Ratso Sloman) still can’t forgive Marty for turning down a life as an executive shoe salesman and refuses to fund another trip overseas. There’s also the regal American businessman Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary), who Marty charms through sheer force of will. Marty’s original motivation is to seduce Milton’s movie star wife, Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow), but when he sees that her husband can provide the necessary capital, he plays those cards as well. The most sporting option for raising money is hustling local ping pong tables with his friend, cab driver Wally (Tyler “The Creator” Okonma).

Because Josh Safdie is a maximalist, we spend the middle ninety minutes of the movie watching Marty explore all of these options to fight his way back to his rematch with Koto. Much like his previous two films, Good Time and Uncut Gems, these schemes all pile atop each other creating a whirling disaster of our protagonist’s own creation. Complications get added such as Rachel’s pregnancy, and his romantic entanglement with Kay Stone, which happens right under the nose of her powerful businessman husband. That he manages to maintain hostile relations with both parties without this affair ever being discovered is an accomplishment in and of itself. Things really take a turn when he encounters a dog-loving criminal named Ezra Mishkin (Abel Ferrera), adding a more sinister element of violence to Marty’s outrageous schemes.

The first thirty minutes and the last thirty minutes of Marty Supreme is a wondrous expansion of Josh Safdie as a filmmaker. The international table tennis sequences showcases a filmmaker ready and willing to upscale from gritty indie director to a large scale auteur. In particular, a short interlude which involves actor Geza Rohrig telling an eccentric anecdote about time spent in Auschwitz is humorous, despairing, and provocative in equal measure. The sequence, early in the film, feels like a sudden narrative shift while being completely in step with the origins and motivations of Marty’s character. The brilliance of the scene not only displays Safdie’s mastery of tone but is evidence of the the scope of his ambition as a storyteller. His interests in a very specific kind of Jewishness is an open challenge to the audience. Like Adam Sandler’s Howard in Uncut Gems, Chalamet’s Marty leans into ethnic stereotypes with no apologies, with Safdie openly provoking the gentiles – root for this person or not, but they are living their lives on their own terms.

Now, there’s still the film’s middile ninety minutes, with Marty running multiple schemes, manipulating every person he sees, in an attempt to get his ticket back to the World Championships. This portion of the movie, which is the film’s majority, felt a bit like a regression for Safide, a return to what makes him most comfortable: an extremely stressful journey through the darkest pockets of New York City, populated with faces familiar not because they’re celebrities (though many of them are – George Gervin! Penn Jilette!), but because their expressions detail a genuine version of New York. In theory, anyway. I’ll confess that I spent a good amount of this portion of the film wishing that I was watching more of the incredible ping pong scenes. Safdie is in his element traversing the various class tiers of NYC, detailing how the elegant rich and the disparate poor create barriers for Marty in equal measure; and the scenes are sufficiently thrilling in their unpredictability. But it felt more like a comfort blanket for a director not quite ready to fully embrace a more mainstream aesthetic.

Even when he was making films with his brother Benny, you could quibble with the methods of a Safdie movie. One of the calling cards of his movies is an intentional lack of discipline both in storytelling and form. Now a solo filmmaker, Josh Safdie has successfully morphed this into a resplendent filmmaking style. One watches Marty Supreme and can hardly remember the junkie grittiness of his 2014 film Heaven Knows What. His collaborations with screenwriter Ronald Bronstein, cinematographer Darius Knohdji, and music composer Daniel Lopatin have only strengthened over time. (Lopatin’s music score here may be the very best of 2025.) Working for the first time with legendary production designer Jack Fisk shows how serious Safdie is about being taken seriously. So there is a little Marty in Safdie himself, and always has been. Like his protagonist, Safdie is dreaming big, and has produced the most ambitious film of his career.

.

Directed by Josh Safdie