And so. In September, my son Orin was born. To say that this completely changed every aspect of my life would be an understatement, but for the purposes of this blog – which I’ve been running in some capacity since 2007 – it means that I got to go to the movies a lot less, if at all, then I usually do. I try to catch things at home, when the rental prices aren’t too high, but generally my maniacal commitment to seeing as much as I can before my end of the year list was halted. This is probably for the best. The compulsive need to go to the movies as many times as humanly possible has brought me great joy but it probably isn’t great behavior for a new dad. So it’s with these qualifications that I bring you my end of the year list, created with the understanding that there is plenty out there in 2025 that I still haven’t seen – and that’s okay! In alphabetical order:

.

.

Blue Moon (dir. Richard Linklater)

The combination of Richard Linklater and Ethan Hawke has brought us some incredible films already, but no one would have expected the timeless brilliance of Blue Moon. “Timeless” is a particular word choice, especially considering Linklater’s obsessions with the ways time is a crucial element in storytelling. For music lyricist Lorenz Hart (played by Hawke), time is vanishing fast. His partner, Richard Rodgers (Adam Scott), has moved onto to another lyricist, and their new play, Oklahoma!, is a major success. Linklater and Hawke show us Hart during a boozy night where he expels witticisms, anecdotes, and personal grievances. Hawke’s performance is a marathon of dialogue as Hart talks and talks and talks, almost in fear of what a conversational lull might mean. Could it mean that time is up for one of the Twentieth Century’s great talents? There’s a glory to the way Lorenz Hart handles himself throughout the film even though we know his peak is well behind him.

.

.

It Was Just An Accident (dir. Jafar Panahi)

When a government leads with intimidation, violence, and cruelty, that reverberates throughout the population. Jafar Panahi has seen this firsthand, having been imprisoned for making films that dared to challenge his country’s government policies. Panahi has the profile of a world-renowned filmmaker. It Was Just An Accident is a film about people who do not have an international reputation to lean on. A man who may or may not be a former state torturer, and a group of people who may or may not have been his victims. Our protagonists feel compelled by moral righteousness even to the point of doing everything they can to confirm this man’s identity before following through on revenge. There’s a moral clarity to Accident, but Panahi is a smart enough storyteller not to be didactic. The cycle of violence created by the state is brought down on the victims and the aftermath is their’s to solve alone. That’s an isolating feeling, and Panahi explores that in an incredibly tense film that still manages to find humor and grace.

.

.

A Little Prayer (dir. Angus MacLachlan)

Family can be a comfort, but it can also be a weight. Few film’s chart that disparity better than A Little Prayer which gives us both the virtues and the burdens of those closest to us. David Strathairn is a business owner in small town North Carolina. He’s mild-mannered, conservative, easy to get along with. His children are another story. In fact, he gets along best with his daughter-in-law (a tremendous Jane Levy), but when he learns that his son is cheating on said beloved daughter-in-law, the sins of his children begin to take on bigger stakes. Angus MacLachlan’s film is a small, quiet feature about a parent who learns a difficult lesson: after spending a lifetime protecting his children, he must now start protecting others from them. Will Pullen, Anna Camp, and Dascha Polanco highlight a great supporting cast, but Celia Weston, as the family’s matriarch, gets best-in-show honors with a performance that is equal parts hilarious and profound.

.

.

The Mastermind (dir. Kelly Reichardt)

The year of Josh O’Connor. Or perhaps we’re only halfway through the decade of Josh O’Connor. He’s shown us that he can give us great performances in a variety of ways. The Mastermind is his collaboration with filmmaker Kelly Reichardt, the masterful storyteller whose pensive, intellectual films are often incisive looks into American culture. This is no different. O’Connor plays an unemployed husband and father who arranges to have some paintings stolen from the local art museum. When things don’t go as planned, he’s forced to deal with the reality of life on the run, free of any romantic outlaw notions. He’s set up like a Coen Brothers protagonist (humorously independent, in way over his head), but Reichardt intentionally removes any possible whimsy. O’Connor’s performance is a perfect capsule of a man coming to terms with his own limitations, forced to realize that the charms and deceptions that have gotten him through life will not always be at his disposal. It’s a remarkable performance in a remarkable film.

.

.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl (dir. Rungago Nyoni)

If A Little Prayer is about a complicated family, then On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is a about a family completely undone by delusion and willful ignorance. This is a comedy about some of the darkest stuff you can imagine. Susan Chardy plays Shula, who, in the film’s opening scene, finds the dead body of her uncle lying in the road. This precedes a days-long mourning ritual in which said uncle’s sexual misdeeds with the many young women throughout the family begin to creep back into everyone’s memory. Director Rungago Nyoni gets some laughs at the pure absurdity with which patriarchal power dominates our day-to-day life; even, somehow, after these monstrous men have passed away. Screened at festivals in the Fall of 2024, A24 in their infinite wisdom quietly released this film in the Spring, one of many (usually foreign) films that the trendy distributor shoots into orbit with little-to-no support. Which is a shame! Because this is the best film they’ve released all year.

.

.

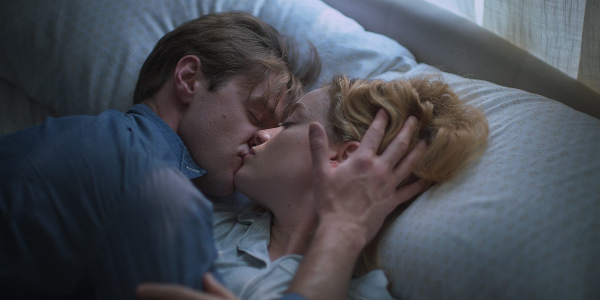

One Battle After Another (dir. Paul Thomas Anderson)

There’s no way to say this without sounding like a gatekeeping jerk, but I remember being a high schooler in 2005 telling anyone who would listen that Paul Thomas Anderson (who at that time had only made four films, including Magnolia and Punch-Drunk Love, two of my faves) was the best director alive and hearing crickets. That changed during my freshman year of college, and There Will Be Blood shot his stock through the roof. But that really changed this September when One Battle After Another easily became his biggest commercial success, while the film itself found essentially unchallenged raves from critics and audiences alike. Talks of a P.T. Anderson confirmed Oscar feels like absolute madness to the high school me. So it’s with all this baggage that I walked into my screening of One Battle After Another two weeks after my son was born and found myself loudly weeping at Anderson’s portrayal of encumbered fatherhood. There’s a reason this movie is being heralded as an instant classic. It is.

.

.

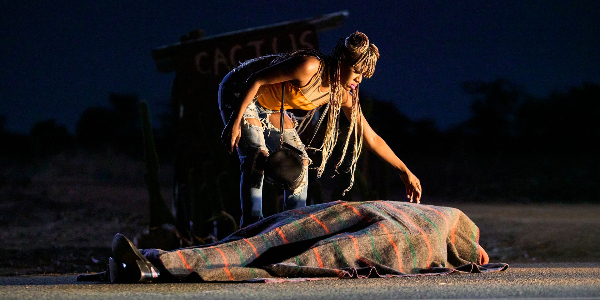

Sinners (dir. Ryan Coogler)

The first two hours of Ryan Coogler’s Sinners is a lush, incredibly crafted genre tale about Jim Crow and supernatural horror – and how little difference there is between the two. “Sinners is a musical!” No, but this movie uses music so incredibly well that I could understand the sentiment. I don’t just mean Ludwig Goransson’s brilliant score, but also the soulful tunes from the smooth-voiced Miles Caton, and even the folksy jigs from Jack O’Connell’s archvillain Remy. This isn’t even getting to the sequence in the middle of the film that is so incredibly audacious and well-executed, I don’t need to even provide anymore details because you know what I’m talking about. There’s the incredible cast. Michael B. Jordan playing twins, while Caton and O’Connell join Wunmi Mosaku, Hailee Steinfeld, Omar Benson Miller, and the phenomenal Delroy Lindo within a great supporting cast. But to me, it’s the film’s final moments – structured more like a coda after the script’s main drama has concluded – that really makes Sinners special. In it, Coogler not only snatches triumph out of the hands of tragedy for his characters, but does so in a way so enlightened and beautiful it felt like a narrative revolution.

.

.

Sorry, Baby (dir. Eva Victor)

Like On Becoming A Guinea Fowl, Eva Victor’s Sorry, Baby has a title that will really throw you for a loop once you learn its narrative context. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that both films are about the aftermath of sexual assault, and that said titles are sobering allusions to the ways infantilization can be a helpful protection against victimization. Victor’s film is also a comedy about similar dark subject matter, though her film is much more cemented in the milieu of American independent film. The jokes come from our protagonist, Agnes (played wonderfully by Victor herself), fighting against the urge to shrink herself in the face of her trauma, since that feels like the easiest thing to do. Agnes struggles with the seriousness of her suffering because the event itself felt so everyday and unexciting; and that’s where Sorry, Baby leaves its teeth marks: in revealing how insidious the ordinary and quotidian can actually be. Naomi Ackie plays a supportive best friend role that feels stock, but actually lends the film some much needed warmth and perspective. She, of course, also ends up being the mother of the titular baby, that receives some wisdom that many girls receive far too late.

.

.

Train Dreams (dir. Clint Bentley)

A wonderful American elegy that mourns the past while accepting its great sins. Joel Edgerton plays a railroad man-turned-logger in the Turn of the Century. His quaint existence is marred by tragedy time and again. His own life, modest and plain, feels small compared to the cosmic forces that batter it from all ends. Director Clint Bentley set out to make a beautiful film, and he succeeded. The Adolpho Veloso cinematography and the Bryce Dessner score are amongst the best of the year; if not the best. Its imagery of American enterprise is equal parts inspiring and despairing. The victories of many often come at the expense of others. Edgerton’s logger learns this lesson one too many times. But Bentley’s film manages to side-step morose drama. His interests instead lie in those brief glimpses of grace that birth themselves from our pain. Train Dreams, in its own loquacious way, argues that America is a nation born out of that pain, and like it’s protagonist, we’ll only overcome it once we’ve learned to accept it.

.

.

.

Weapons (dir. Zach Cregger)

One of the best performances I’ve seen in any movie this year is Amy Madigan in Weapons. She plays Gladys, the main villain, a terminally ill woman with supernatural powers that she uses to stem the tide of her sickness. We don’t meet Gladys until about halfway through the movie, and even later we learn that she’s the one who caused the film’s singular event: seventeen grade schoolers waking up at the same time in the middle of the same night and running away from home. She coerced the children with sorcery in a ruse to keep herself alive. Before learning this, Zach Cregger’s script is masterful in keeping the creepy mystery afloat, watching as each idiosyncratic character adds layers to this untrusting setting. Usually, when a horror film reveals that it’s merely a witch (or a goblin some other cosmic contrivance), you end up losing all the juice from the film’s preceding mystery. And that’s why Amy Madigan’s performance is so spectacular. Her performance perfectly transitions Weapons from a suburban horror comedy into a devastating character drama about an unloved monster. And the fact that it works takes Weapons from another “elevated horror film” to one of the best films of the year.

One Last Thing…

You expect to learn a lot from becoming a parent. It’s one of those things that all parents say. My life has transformed completely. My expectations of myself and my life have transformed completely. I went to film school but learned early on that I had little interest in actually making movies, I just wanted to watch them. And that’s basically all I’ve done for the past two decades of my life. Don’t get me wrong, I met my wife fourteen years ago and we’ve been quite happy that entire time. I’ve moved across the country. I’ve purchased a home. I’ve lived life outside the movie theater, but with every step, the back of my mind was always creeping back into the darkness and the big screen. After my son was born in September, it was the first time that there was really anything that took major precedence over that. I’ve been to the movies once since then (to see One Battle), and I spent a majority of the runtime worrying about what I was missing at home. Is this the new normal? We’ll see. I still watch plenty at home, and I still love to write about what I see. And I’ll be back to the movies again. So this site isn’t going anywhere. But for the last three months I’ve gotten to see what my life would be like if I wasn’t forcing myself to be obsessed with movies and instead being obsessed with my kid. And you know what? Not too bad.