“I’m never serious about anything.” – Warren Beatty as George Roundy in Shampoo

Set on the day of the 1968 Presidential Election, Shampoo gives itself the benefit of hindsight. Released in 1975, the film’s characters traverse across Los Angeles, the background noise harangued by television news stations announcing the surge of Richard Nixon’s forthcoming election. It’s a deliberate point in Shampoo that the characters almost never talk about it, that the vain, attention-starved people often treat the election like it’s an extra in a movie about their lives. Which it is. This vision of Southern California is not unique but it is awash in details that spell out exactly how the dream of the Sexual Revolution was lost. In a culture where substance is compromised for titillation, what other fate could there be?

The film was developed by megastar Warren Beatty, and here he got his first producing credit since Bonnie and Clyde in 1967. It’s a testament to Beatty’s industry influence at the time that he is able to share a screenwriting credit here with Robert Towne, no easy feat as Towne was not normally in the business of sharing credit and he was recently hot off the success of his greatest script Chinatown (where Towne is solely credited as the writer despite much help from director Roman Polanski). Like Chinatown, Shampoo gives us a hazy, cynical view of Los Angeles, a vast city filled with vapid secrets and even more vapid people. In Chinatown, personal and political scandal play out before the advent of World War II. In Shampoo, sexual politics consume the minds of so many people, they can’t see Nixon-Agnew for the trees.

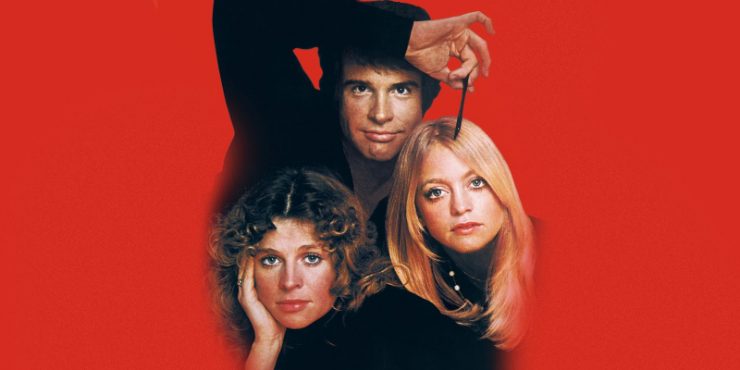

Beatty is George Roundy, a hairdresser and ladies’ man, overworked and over-sexed. George is tangled between several women, including a young actress named Jill (Goldie Hawn), a married woman named Felicia (Lee Grant), and an old flame named Jackie (Julie Christie). To make things more tangled, Jackie has just started a relationship with an older business man, Lester (Jack Warden), Felicia’s husband. None of the women hold exclusivity on George, as his good looks and his occupation’s close proximity to gorgeous girls keeps him in almost frequent courtship. George’s real dream is to open a shop of his own and be his own boss, but a bank loan seems far out of reach with his lack of business experience. George believes he has a committed enough clientele to sustain his own shop, but whether those clients prefer his talent in the salon or in bed is coyly left for the audience to decide.

The film is directed by Hal Ashby, an editor turned quintessential 70’s director thanks to the quirky Harold & Maude and the brash The Last Detail (also written by Towne). His films, though seldom possessing strong cinematic style, were often tinged with political awareness, whether it be the overt Vietnam polemic within Coming Home or the desert-dry satire of Being There. Shampoo, a film both romantic for and disdainful of California’s welcoming pre-Manson lifestyle, fills itself with imagery meant to draw us toward a specific irony: the free love era was hijacked by some very sinister people who were waiting to get in through the door while people were busy getting their rocks off. America was teetering between the reckless abandon of George and the conservative market obsession of Lester, and the Lesters won big time.

While George and Lester seem to represent polar opposites, they actually both covet the same goal: financial success. Lester has achieved it, and sees the possibility of sustaining it with a Nixon presidency (he’s the only character I noticed to speak directly about the charged climate). George sees financial independence as the ultimate goal, but for him it is much more unattainable. His inability to keep it in his pants seems to spoil a lot of opportunity for him, and even when it does seem like he’s acting out against staunch types like Lester, he is always quick to remind the audience otherwise. “I’m not anti-establishment” he says flatly in the film’s third act. George’s character is forecasting the 60’s windfall into capitalist greed and Lester is the kind of man that will take him there.

But for all of Shampoo‘s posturing about political apathy, George and Lester seldom rise above symbolism, always at the mercy of the women who drive them wild. Which is why the women are so much more interesting to watch. While all driven crazy by the philandering of men, Jill, Jackie and Felicia are still much further expanded as characters, and the performances from Hawn, Christie and Grant (who won the Oscar for this) are so much richer. Hawn, usually a master of comedic timing, instead excels in the more dour role: confused ingenue who learns early that her trust is too valuable to waste on George. Grant, wonderfully funny and vulnerable, takes all of the shrillness out of the scorned-wife role and instead becomes scorched-Earth. Christie, in a bit of a confused role, fully embraces the film’s sexuality and potently portrays a woman dashed between two dreams. Like George, Jackie is torn between her practical needs and her desires, but she possesses a much shrewder mind.

One can make arguments against Shampoo‘s gender politics, its latent (though sometimes not so latent) homophobia, or its frequent appeals to Beatty’s vanity. The script’s pointed criticism of a specific past feels like such a morose indictment of a disappointing present. What Shampoo could not have predicted was how the film, in 1975, was itself on the precipice of another cultural shift, with the provocative work of New Hollywood clearing out for the commercial filmmaking of Spielberg and George Lucas. The Me Decade would be laying out the red carpet for Reaganism. As a film made with hindsight, it is now a much more interesting film about foresight, and the futility of good intentions. At the film’s conclusion, Beatty’s George is left alone near the top of one of those notorious Los Angeles hills looking off into an uncertain future. A future Shampoo saw much clearer than it realized.

Directed by Hal Ashby