1. Moonlight

1. Moonlight

Directed by Barry Jenkins

“Who is you, Chiron?” The protagonist of Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight is asked this directly toward the end of the film, and it’s the culmination of a film-long search. We see Chiron at three different ages: as a child (Alex Hibbert), as a high schooler (Ashton Sanders) and then as a fully-formed adult (Trevonte Rhodes), and in all three stages he searches for peace and self-acceptance as a gay black man living in Liberty City, a decaying ghetto outside of Miami. Jenkins’ film is stunningly beautiful, and a crowning achievement for all involved. It speaks toward the struggle for marginalized people, as a young man learns that not every personal truth will be accepted by those around him. Of course, his surroundings are no help. He is constantly bullied at school, his father is out of the picture, and his mother (Naomie Harris) is a struggling addict who abandons Chiron at his most emotionally needy. One of his few sources of support is a local drug dealer (a phenomenal Mahershala Ali), but that relationship ends much too soon. Jenkins’ script (based on an unproduced play by Tarell Alvin MaCraney) is equally heartbreaking and affirming, and his film is astonishingly well-made. Moonlight felt to many like a landmark, a document of a story too seldom told, and its this uniqueness that let this film find its audience.

2. Krisha

2. Krisha

Directed by Trey Edward Shults

Many don’t look forward to Thanksgiving with the family, but this debut film from Trey Edward Shults is a home video of existential dread. Casting most of his family and filming in his childhood home, Shults tells the story of Krisha (Krisha Fairchild, Shults’ aunt), a troubled woman coming to Thanksgiving in an attempt to make amends for past misdeeds. Shults himself plays Trey, Krisha’s embittered son, while the rest of the Thanksgiving family includes Shults’ mother, Robyn Fairchild (as his aunt) and various cousins and uncles and grandmothers and in-laws. The degree to which the reality of Shults’ turbulent family life overlaps with the fiction of the film is hard to judge, and that mystery adds to the tense, off-balance nature of Krisha‘s brilliance. The movie is an 83-minute panic attack, with one woman’s desperate attempt to try and be part of a family that has left her behind. To fit into this family – a family predisposed to see the worst in her – she must behave like somebody else. Fairchild’s performance is a stunning portrayal of pride-swallowing vulnerability, a performance of a performance. In the end, old habits die hard, and Krisha’s attempt to make herself presentable has disastrous consequences.

3. O.J.: Made in America

3. O.J.: Made in America

Directed by Ezra Edelman

I watched O.J.: Made in America as a five-part series on ESPN, which is how most people saw this absolutely absorbing, point-by-point break down of the O.J. Simpson murder trial. It’s probably not fair to call it a film, even though the entire 7.5 hour film did play in theaters, and there were some people crazy enough to sit through it. Whether it’s a film or a television series, what’s indisputable is that Ezra Edelman crafted a masterpiece about the way race finds its place in every crevice of American life: in our sports, in our entertainment, in our crime, in our love. Edelman took a deep dive into something that has been examined and re-examined hundreds of times (including a hit FX mini-series The People v. O.J. Simpson which played earlier in the year), and came out with something completely unique. We’re no longer suffering over the question of “did he do it?”, but examining all of the players, all of the parties, some of them innocent most of them not. Made in America is not a search for heroes, but a macro exposure of the cruel irony within the American justice system. Edelman’s saga doesn’t teach you much more about Simpson that you probably didn’t already know, but it places it in a context seldom shown, as a diagram for America and its disturbing history with race.

4. The Lobster

4. The Lobster

Directed by Yorgos Lanthimos

Yorgos Lanthimos made one of the most disturbing films I’d ever seen with Dogtooth, so it makes a lot of sense that The Lobster would be his version of a love story. Filled with black humor, and a terrific ensemble of performances, Lanthimos’ latest feature is a ferocious satire aimed directly at love. Colin Farrell plays our protagonist, a pot-bellied man with a flat personality. When he’s dumped by his girlfriend he is sent to The Hotel, where all single people are sent, where they have thirty days to find a new partner, or they get turned into an animal. The Hotel is filled with lost souls, like a man with a limp (Ben Whishaw) and a woman that is completely heartless (Angeliki Papoulia). When he escapes the hotel to find a group opposed to the dictatorial ways of The Hotel, he meets a woman (Rachel Weisz) who is perfect for him, only to learn that his new group a friends oppose love even stronger than the hotel enforced it. The Lobster‘s unique portrayal of love – draconian, tyrannical, the root of all human problems – is what sets this fiercely mannered comedy apart from other loopy love stories. Lanthimos crafts such an interesting, distinct universe, backed by a cast so efficient in making that world a real place. The Lobster was the best comedy of the year, that’s sure, but it is also amongst the year’s most unsettling.

5. Hell or High Water

5. Hell or High Water

Directed by David MacKenzie

No other movie in 2016 better documented the spindling contradictions of America than David MacKenzie’s Hell or High Water. The movie speaks with the scope of John Steinbeck (thanks to a brilliant script from Taylor Sheridan), but hits hard with the power of the Coen Brothers’ most ferocious dramas. Two brothers (Chris Pine, Ben Foster) begin robbing banks in an effort to defraud the very institutions that preyed upon their frail, recently deceased mother, and left the family in crippling debt. On their trail is a hangdog sheriff (Jeff Bridges) with retirement in his sights, who grabs one last juicy case before heading out to pasture. MacKenzie and Sheridan are touching on so many aspects of twenty-first American culture, and they place that story in Texas, perhaps this troubled empire’s most complicated state. It’s interesting to think about this film after Trump’s election, as so much of it is a cry for help from the very Americans who may have been suckered by that political demagogue. In many ways, Hell or High Water is a prescient portrayal of a certain portion of America quickly getting left behind. Hell or High Water is a fascinating critique, led by a brilliant trio of performances, so unique, yet so in sync with the movie’s themes and narrative.

6. The Handmaiden

6. The Handmaiden

Directed by Park Chan-Wook

I no longer have to wonder what a love story from Park Chan-Wook would look like. The notoriously bloody filmmaker behind Oldboy and Lady Vengeance brings us The Handmaiden, a sultry, funny tale of multiple duplicities within Korean aristocracy. A Korean petty thief (Kim Tae-ri) agrees to join forces with a charismatic con man (Ha Jung-woo) in a complicated scheme to withhold a nice pay day from a Japanese heiress (Kim Min-hee). The plan works and doesn’t work in various ways, and the film’s script (by Park and Jeong Seo-kyeong) is fit into a revolving three-part, novel-esque saga that keeps the audience guessing until a conclusion that is amongst the most satisfying of any this year. The Handmaiden still contains elements of Park’s usual emotional dysfunction, and while Park is (for the most part) turning away from his usual calling card for bloody violence, he more than makes up for it with sexual and emotional graphicness. But the graphicness is all connected by a romance between our two female leads. Kim Tae-ri and Kim Min-hee’s portrayal of passion within a dangerous, complicated world of men is something to behold. We’re left with a terrific film about two women’s fight against an oppressive patriarchy, as well as a fight to preserve and legitimize the love they feel for one another.

7. Manchester by the Sea

7. Manchester by the Sea

Directed by Kenneth Lonergan

Kenneth Lonergan could never be said to be a particularly sunny filmmaker, but Manchester By The Sea leads his previous two films in devastation – and that’s saying something. This is his third film, which is important considering that it’s also his third masterpiece, another segment in his ongoing study of human pain and existential suffering. Manchester focuses mostly on guilt, particularly that of Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck) a Boston janitor who returns to his hometown, Manchester-by-the-Sea, after his brother (Kyle Chandler) dies and he is named guardian of his nephew Patrick (Lucas Hedges). Lee has been living a life of self-imprisonment which is suddenly disrupted as he tries to settle the hectic home situation. A past sin may come back to haunt him. This is human drama like only Lonergan can pull off, a form of hyper realism that can almost feel like melodrama. Affleck’s performance is so acutely painful to watch. He’s a man who’s very bodily function does not allow him to forgive himself for his past. Lonergan crafts the film with care, building around Lee’s mourning with flashbacks to Lee’s Big Sin, leading toward a reveal more devastating than anything else I saw this year. A supporting performance from Michelle Williams – as Lee’s ex-wife – is short but brilliant, an innocent bystander in Lee’s broken life.

8. La La Land

8. La La Land

Directed by Damien Chazelle

La La Land has been running on the premise that it is bringing back the classical music, which isn’t false but belies the refreshing feeling that comes over you when you see this film. Chazelle’s follow up to 2014’s Whiplash couldn’t be more different in terms of tone, and also couldn’t be more delightful. Charting a love story between a jazz pianist (Ryan Gosling) and an aspiring actress (Emma Stone) as they toil away in the grind of sunny Los Angeles, La La Land is a testament to youth, cinema, great music and the rapturous joy and terrible pitfalls of love. Songs by Justin Hurwitz, and sharply choreographed dance numbers pump in and out of the film, perfectly displaying Chazelle’s contrast of the fantasies we all dream about and the realities of life. Chazelle’s script is funny in a very bittersweet way, and heartbreaking in a way that will make you smile, and led by the unbreakable chemistry between Gosling and Stone, La La Land is one of the year’s greatest treats. Stone, in particular, gives a performance the pushes her past movie star status and into the realm of our greatest American actresses.

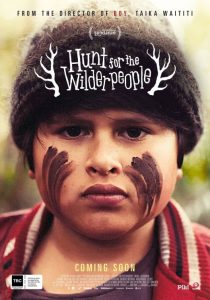

9. Hunt for the Wilderpeople

9. Hunt for the Wilderpeople

Directed by Taika Waititi

I didn’t foresee the cinematic duo of Sam Neill and Julian Dennison to be my favorite of the year, and yet, here we are. The two actors – one a 69-year-old veteran known for Jurassic Park and the other a 14-year-old newcomer – create such a sweet, fascinating chemistry throughout Wilderpeople, the latest comedy from Taika Waititi, who manages to recall here the great comedies of Wes Anderson without the emotional sterility. Dennison plays Ricky a preteen foster child whose bad behavior has gotten him bounced around through many homes who quickly tire of him. When he ends up in the custody of Hec (Neill), he finally finds someone he can call family. When a zany set of circumstances send them into the woods, child services begin looking for them, and the search quickly mushrooms into a full-blown manhunt, as Hec and Ricky are suddenly forced to survive in the wilderness in order to stay together. Wilderpeople is absurd, hysterical, stunningly poignant at times, and completely lovable. Dennison’s performance as the hip-hop loving Ricky is one of continuous surprise, getting better with each scene. More than anything, it’s Waititi’s treatment of the story that stands out. No matter how wacky the story becomes, he stays in touch with their humanity.

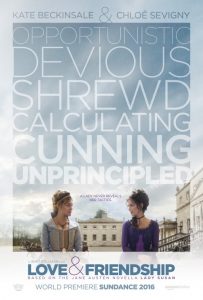

10. Love and Friendship

10. Love and Friendship

Directed by Whit Stillman

Whit Stillman takes the charm of Jane Austen and turns up the absurdity in this charming, hysterical comedy. Taking the novella Lady Susan, Stillman crafts the tale of Lady Susan Vernon (Kate Beckinsale) a diabolical woman capable of the most daring deceptions. With a dead husband on one end and a scandalous affair with a married man on the other, Lady Susan retreats to Churchill, where she will stay with in-laws as she plans a way to solve her current social and monetary problem. She weaves in and out of various aristocratic families, hoping to either find a capable husband for herself, or at the very least find a very rich husband for her daughter (Morfydd Clark). A couple of the eligible suitors are a handsome, naive bachelor living in Churchill (Xavier Samuel), as well as a shockingly dim man (Tom Bennett) who happens to have a lot of money. A brilliant ensemble also includes Stephen Fry, Emma Greenwell, James Fleet and a terrific Chloë Sevigny as an American expatriate who is Lady Susan’s most loyal ally and most willing gossip hound. Stillman’s film is a refreshing take on Austen, a shunning of the sincerity of our most recent adaptations. Beckinsale’s Lady Susan is a tremendous, hilarious portrayal of vanity, while Bennett’s performance of stupidity may just be the most intelligent performance I’ve seen in a movie this year.