If Spike Lee’s form of provocation seems on-the-nose, it’s only because the world has caught up to his particular vision of our culture. Lee has often been controversial, has been accused of paranoia, charged as a muckraking storyteller only interested in stirring complicated emotions and offering no solutions. He’s never seemed to care at all how much you like his films, and particularly these days many will line up around the block to tell you what is wrong with them politically, aesthetically or otherwise. Lee is, and always has been, playing the long game. His films – especially the great ones like Do The Right Thing and Malcolm X – age into our consciousness, and with time they seem less like fire & brimstone proclamations and more like desperate pleas to act against a monolithic system. So maybe it’s fitting that Lee is looking into the past, in his latest film BlacKkKlansman, to tell us about today.

The film is based on the memoir by former Colorado Springs police officer Ron Stallworth (John David Washington, son of Denzel), the county’s first black policeman. Working his way up from the records room, Stallworth nabs himself an undercover position within the city’s chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. Stallworth’s blackness being an obvious impediment to the investigation, the CSPD sends a white officer, Detective Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver), to be the face to Stallworth’s lucrative voice. The pair work out the logistics and manage to get deep within the local chapter, and Ron even gets himself into a cozy telephone relationship with the KKK’s grand wizard (though for PR reasons, he prefers the title National Director) David Duke (Topher Grace, in a performance that’s almost too good). With the KKK’s ambitions toward igniting a long-gestating race war, Stallworth and Zimmerman work their way into danger in order to stop the malice from erupting.

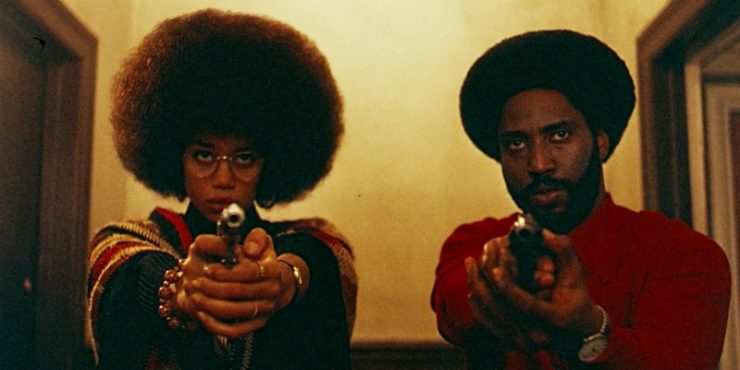

Stallworth is also asked to infiltrate a Stokely Carmichael rally, where he meets Patrice (Laura Harrier), the head of the Black Student Union at Colorado College. Patrice welcomes Ron’s offbeat charm, seems almost amused by his centrist politics, and relishes the opportunity to bring him into a more radical view of black politics. Carmichael, now going by Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins), gives a rousing speech about the need for blacks to arm themselves against an oncoming war. Stallworth can see the difference between Ture and Patrice’s Black Panther movement and the hatred of Duke and the KKK, but still believes he can make a difference within the police force – a notoriously racist institution. Playing undercover on two accounts (and using his actual name in both instances), Stallworth’s situation becomes more complicated. Add to that some within the Klan who are skeptical of Flip’s cover, and the officers begin to face actual danger.

All of Spike Lee’s films are in some way about race, but they are also always about the movies. He cherishes films, holds a particular reverence for film history, but is also one of the medium’s most scathing cultural critics. Lee has often been a master of taking the tactics of (white) Classic Hollywood and deconstructing it, bending it to his will to expose a hypocrisy within the liberal industry’s politics. Throughout BlacKkKlansman, we see images of Victor Flemming’s Gone with the Wind and D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. Both movies were titanic box office hits. The first film won the Oscar for Best Picture, and the second one certainly would have if the Oscars had existed at that time. They also played heavily into America’s movement of re-legitimizing white supremacy in the early twentieth century, and gave credence to a hateful group to rise from the shadows. Movies have power, and Lee knows this.

Lee repurposes that history, and also tackles contemporary Hollywood’s luxuriation of white racism, its penchant for making racists more captivating in the movies than their victims. He seems to care little for the subtle nuances of your everyday racist, and takes no glimpses of the humanity that may linger beneath. The racists of BlacKkKlansman are basically as cartoonish as the black characters in Griffith’s Nation. This is epitomized by the character of Felix (Jasper Pääkkönen), the kind of racist that this story seemingly can’t be told without. Felix seems to run only on hate, his entire being filled with prejudice. From the start, he is skeptical of the Ron Stallworth that he meets, frequently accusing him of being a Jew. If Lee sees the character of Felix as some kind of narrative requirement – a one-dimensional villain whose only service to the plot is ugliness – then he chooses also to max out that requirement, to make him as unpleasant and one-dimensional as one can.

There is room to quibble over details and the ways in which the story is told. Sorry to Bother You writer-director Boots Riley already gave us a three-page critique of the film’s apparent historical miscues. BlacKkKlansman‘s tight-rope walk in terms of viewing the police force as inherently racist and also a useful tool for change doesn’t exactly ring true, nor does it play in tune with the films of Lee’s heyday. Stallworth’s dogged commitment to the force is played as honorable even in the face of constant evidence of prejudice. Getting upset over Lee changing facts or playing fast and loose with the actual story seems arbitrary, the film kicks off with a feeling inherent absurdity which doesn’t relent until one of those patented somber codas that Lee loves to pin at the end of his movies. It’s easy to see Lee connect the dots for you and feel like he doesn’t trust his audience, but when you see the way some willfully misunderstand his stories, wouldn’t you have those same trust issues?

BlacKkKlansman pays off for those who saw 2015’s Chi-Raq and believed the more audacious, grandiose Spike had returned. Not all of Lee’s politics have aged into millennial culture with perfect ease. There are many who would like to see him collect his chips and go home. I have an affection for his refusal to do so, for his insistence on being part of the 2018 conversation, the same conversation he’s been trying to have since the mid-80’s. His aesthetic, so fierce and so evocative, has always felt alive to me, translatable to any time. His decades-long relationship with composer Terence Blanchard and editor Barry Alexander Brown have established his cinematic vision, creating in BlacKkKlansman a kind of culmination. Lee cannot help but directly draw the lines between the KKK and Trump (that he seems unwilling to do the same with the police is a conversation worth having), but it’s that kind of ham-fisted, demonstrative storytelling that has made his voice so unique. He will never take his hands off your collar and will never stop pleading with you to WAKE UP.

Directed by Spike Lee