The writing life is a lonely one, contending with the voices in your head more than the people in your life. The protagonist of American Fiction, Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, is a published author whose fallen short of commercial success. This has turned him bitter, with a particular frustration aimed at the publishing industry that downplays Black authors, unless they’re writing about poverty or gangland violence. By the time we meet Monk his mind is solidly made up, and he can’t envision a redemption for a trade profession that passes him over for worse writers with cliched stories. His stubbornness manifests itself in a hostility towards those he loves most. Living a life of rejection, he then turns that rejection over onto them, which doesn’t make spending time with him very enriching.

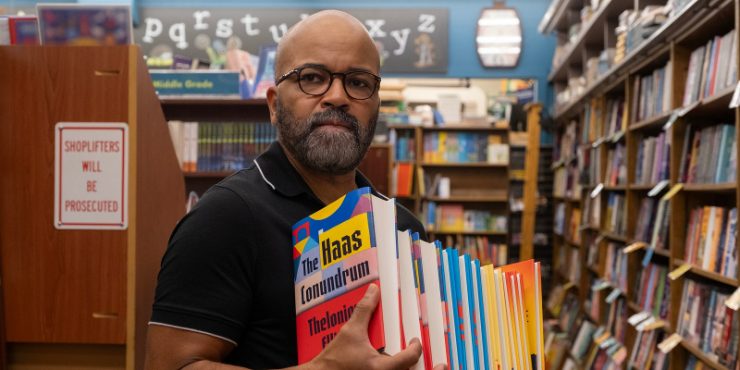

This is perhaps why the film casts Jeffrey Wright to play him. Wright is an actor of great versatility and elegant delivery, and his ability to work well between comedy and drama has made him one of the most dependable character actors of the last three decades. He’s a performer that can commit wholly to Monk, detailing his many faults, without alienating an audience. His natural charm and unmatched eloquence is always fascinating to watch (case in point, watch his stunning monologue in Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City from earlier this year and try not to be completely transfixed). His performance in American Fiction is a particularly great showcase for everything he has to offer, and one of the few times he’s gotten the opportunity to lead a film (if I’m not mistaken, the first since 1997’s Basquiat). Writer-director Cord Jefferson is telling a story but he’s also honoring the strength of Wright’s career, encapsulating everything the great actor possesses in a single film.

American Fiction is the directorial debut from Jefferson, a writer who cut his teeth on television comedies like Master of None and The Good Place, before winning an Emmy for his work on the HBO drama Watchmen. His script – which is based on the novel Erasure by Percival Everett – is a family dramedy wrapped in a satire. It’s provocative premise will remind some of the novels of Ralph Ellison and Paul Beatty. Namely, comedies about white guilt run amok and the false seduction that Black artists can somehow profit from it. At the beginning of American Fiction, Monk is teaching a course in Literature from the American South. When a white student objects to having to read stories that use the N-word, it doesn’t take much for Monk to explode at the narrow-mindedness. The incident (presumably just the latest of many), causes his administrator to force a leave of absence. Some time off to settle down.

Monk then attends a book conference in Boston, which also happens to be the location of his dysfunctional family. His sister, Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), is recently divorced, as is his younger brother, Cliff (Sterling K. Brown). Cliff’s marriage ended after his wife discovered that he was gay, a detail that only further alienates Cliff from his difficult parents. Their mother, Agnes (Leslie Uggams), is starting to show signs of dementia, while their father committed suicide years before. With Agnes’s health declining rapidly, Lisa implores Monk to spend his newfound free time with her, and planning next steps. Adrift and unsure how to proceed – and filled with decades of resentment – Monk angrily writes a book filled with so many Black stereotypes that he cracks himself up in the process. In protest, he sends the manuscript to his agent, Arthur (John Ortiz), who reads the pages – titled “My Pafology” – agog at what do with them.

Monk demands that it be submitted, a thumb in the eye of publishers who don’t value true Black writers. The film takes a major turn when “My Pafology” actually gets picked up by a publisher who offers Monk the largest purchase fee that he’s ever seen. Of course, Monk penned it under a pseudonym, and at the advising of Arthur, Monk must play the part of the hard-edged gangbanger that the book suggests. Monk objects to it all, but with his mother’s medical bills quickly growing, he decides to play the part for editors and film producers willing to write him checks for the worst book he’s ever written. As the book’s popularity skyrockets, he strains to maintain his dual personalities, and the stress only exacerbates his already tense relationship with his family, who need his financial support more than ever.

Jefferson definitely places his thumb on the scale as far as the satire is concerned, but one of the joys of American Fiction is the ways Jefferson writes his way out inevitable corners. His first feature, the alacrity of the screenplay is impressive indeed, signaling a new, unique voice in comedy. It becomes obvious that Monk’s literary gambit is less important to Jefferson than the familial intrigue: the generational tension between parent and child, the never-ending competition between siblings. This is the heart of American Fiction‘s story, and Jefferson is smart to make it more than just b-plot exposition. There is also a subplot involving a recently divorced woman named Coraline (Erika Alexander), one of Agnes’s neighbors whom Monk begins a romantic relationship. Coraline offers Monk a path toward intimacy and acceptance, the very things he’s been running away from his whole life.

The sardonic humor, the punchy jazz score (by Laura Karpman), and the maturity of the narrative reminded me a lot of Alexander Payne’s best work. Like Payne’s Sideways, American Fiction has a soft spot for a lonely, ornery aesthete barreling forcefully toward the doldrums of middle age, and in both instances, the directors were able to find something imminently watchable (if not exactly noble) in these men. Jefferson’s film is more soulful, if not as polished, and his ear for humor does have the steadied rhythm of a veteran. This is a very strong debut, filled with wonderful performances, none more so than Wright. The film feels like a proper announcement of the actor’s incredible (and incredibly modest) career. So often he has been taken for granted. But not here.

Written for the Screen and Directed by Cord Jefferson